What next for the cobalt market?

News Analysis

23

May

2025

What next for the cobalt market?

All eyes are on the DRC as the market awaits its next move on export restrictions for cobalt hydroxide.

In February 2025, the DRC imposed a four-month export ban in response to a sustained period of low cobalt prices and oversupply.

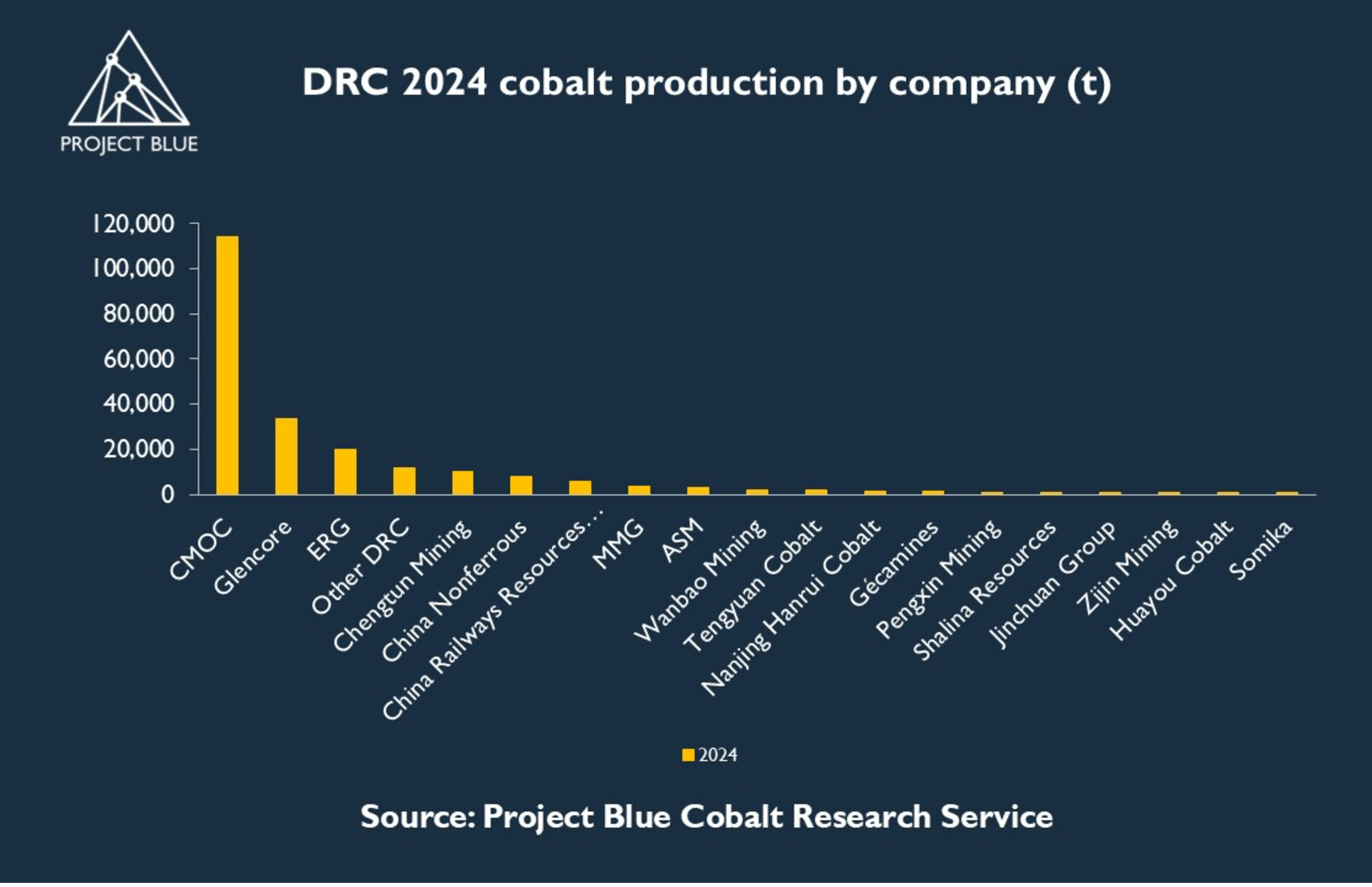

Record levels of mine production in 2024 left the intermediates market considerably oversupplied, with an estimated 75–100 kt of cobalt in hydroxide form sitting in stockpiles. The DRC produced 72% of global cobalt mine supply in 2024.

Despite record output, government tax revenues from cobalt halved between 2023 and 2024 due to depressed prices. This, alongside a broader aim to promote local value-add activities, prompted intervention – and so far, those interventions are having an effect.

Ex-DRC stockpiles are being drawn down, although the timeline to reach ‘critical levels’ remains unclear.

That’s partly because the volume of material in warehouses outside China at the time of the ban is difficult to estimate. Some cobalt also continued to flow into China after the 22 February deadline due to valid paperwork, with Chinese customs data showing imports of 51kt (gross) in March.

The DRC government is expected to announce its next steps on 22 June. Market consensus anticipates a 2–3-month extension of the cobalt export ban, followed by the possible rollout of other export control mechanisms.

Project Blue expects stockpiles could reach very low levels in Q3 if the export ban is in place for seven months and no new material leaves the DRC. With cobalt hydroxide taking roughly 90 days to reach China for refining, exports will need to resume during Q3 else refined production will be impacted.

The DRC government has several typical options for managing exports:

1. Export requirements – setting minimum conditions for exporters, such as sustainability standards or community contributions.

2. Export quotas – limiting the volume each exporter is permitted to export.

3. Production quotas – restricting overall extraction volumes (difficult to implement for cobalt produced as a by-product of copper mining).

While the government’s actions thus far have had a positive impact on cobalt prices, these policies are not necessarily sustainable.

- In-country inventories continue to build through this period and remain an overhang on cobalt prices. Challenging overland logistics are such that not all stockpiles would flood the market at once, but as was seen after the lifting of CMOC’s nine-month export ban in 2023, the cobalt units can find their way back to market more quickly than people expect.

- A blanket ban is easier to police than a quota system. Enforcing export controls can be inefficient and costly for authorities, and without strong enforcement, material may leak out through informal channels.

- While higher prices may be a goal, it is not clear at what price level the government would be satisfied. OPEC+ members have at times expressed oil price target levels, which allows the market to adjust expectations. The risks from significantly higher cobalt prices could be demand destruction or an increase in artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) activity, both of which create additional volatility for industry participants.

These measures form part of a broader effort by DRC policymakers to capture greater value from its abundance of cobalt reserves. The government – typically via state-owned Gécamines – has been negotiating with companies to acquire stakes in existing operations or secure marketing rights to production.

There is also talk of potential consolidation, and smaller hydroxide plants may face licence reviews or revocations.

At the same time, through Entreprise Générale du Cobalt (EGC) – granted a monopoly on the purchasing, processing and marketing of artisanal cobalt in 2019 – the state continues to pursue full control of ASM output to the market.

Whether and how these policies are implemented remains to be seen. But one thing is clear: the cobalt supply chain continues to be unsettled by the sheer level of supply concentration from a single country.