How has Chinese demand for nickel pig iron influenced cost margins and market share of varying refined class products in recent history?

Opinion Pieces

30

Oct

2024

How has Chinese demand for nickel pig iron influenced cost margins and market share of varying refined class products in recent history?

All cost values stated in this article are All-In Sustaining Costs (AISCs) on a CIF basis in US$/t Ni within all feedstock or product types on a pro-rata basis unless otherwise stated.

This work is a continuation of Project Blue’s cost analysis of the nickel market, turning the attention from the extractive nickel sector to the refining industry and identifying trends or differences across the supply chain.

Refined nickel products are typically split into two forms: Class I (>99.8% Ni) and Class II (<99.8% Ni). The former, historically accounting for a larger share of global refined nickel supply, was popular owing to its flexibility, given that it can be used in a wide range of end uses such as stainless steel, batteries, and applications requiring higher purity. Whereas, in recent years, Class II nickel has dominated global supply growth, driven by demand from the Chinese stainless steel industry.

Refined nickel has long been produced from matte via the smelting of sulphide concentrates. However, over recent years, producers of Class I nickel and nickel sulphate have started to use matte produced via converted nickel pig iron (NPI), which has acted as a stopgap for their feedstock requirements, particularly for sulphate producers. This process utilises the low-cost nickel-iron alloy produced at rotary kiln electric arc furnaces (RKEFs) in Indonesia and produces a high-grade nickel matte, which is increasingly used to create nickel sulphate. This has started to blur the traditional divisions between the Class I and II nickel markets. At the same time, to meet the rising demand for sulphate products, predominantly used in the EV battery supply chain, Indonesia has constructed new high pressure acid leach (HPAL) plants, providing additional intermediate feedstock in the form of mixed hydroxide precipitate (MHP). Class II nickel is now almost entirely dominated by NPI (a low-grade ferronickel) produced in Indonesia and, to a lesser extent, in China, owing to demand from the Chinese stainless steel sector. In line with this expanding Chinese demand and closures of high-cost Class I nickel capacity, Class II nickel supply overtook that of Class I in 2016, and its dominance has been increasing ever since.

For the context of this article, nickel sulphate is presented as its own category, produced via intermediates and the dissolution of metal powders, and not included as either Class I or Class II.

Class I vs Class II: China shapes the market

As a result of Indonesia’s strict ore trade policies over the past decade and increased Chinese demand for low-cost laterite ore used in NPI production, investment by Chinese players in nickel processing facilities in Indonesia has been extensive. This has resulted in domestic refined nickel production growing by almost 600% since 2017. In 2023, Class II nickel products accounted for 51% of the refined market, compared to 29% in 2017. As a proportion of the Class II market, China and Indonesia maintain 100% of global NPI production, with respective market shares of 22% and 78% in 2023, compared with 61% and 39% in 2017. The shift in the market dominance of NPI production has occurred due to a combination of massive demand from China (importing nickel laterite ores for domestic NPI production) coupled with the implementation of a series of Indonesian domestic trade policies, strengthening Indonesian production (read our prior note for further context).

As market share increased, Chinese and Indonesian producers saw their profit margins improve considerably. From 2017 to 2023, profit margins, on average, increased for Chinese NPI producers from -7% to 33% and for Indonesian NPI producers from 20% to 33%. These increases highlight the beneficial impact of lower-cost laterite feedstock, leading to a direct increase in market share.

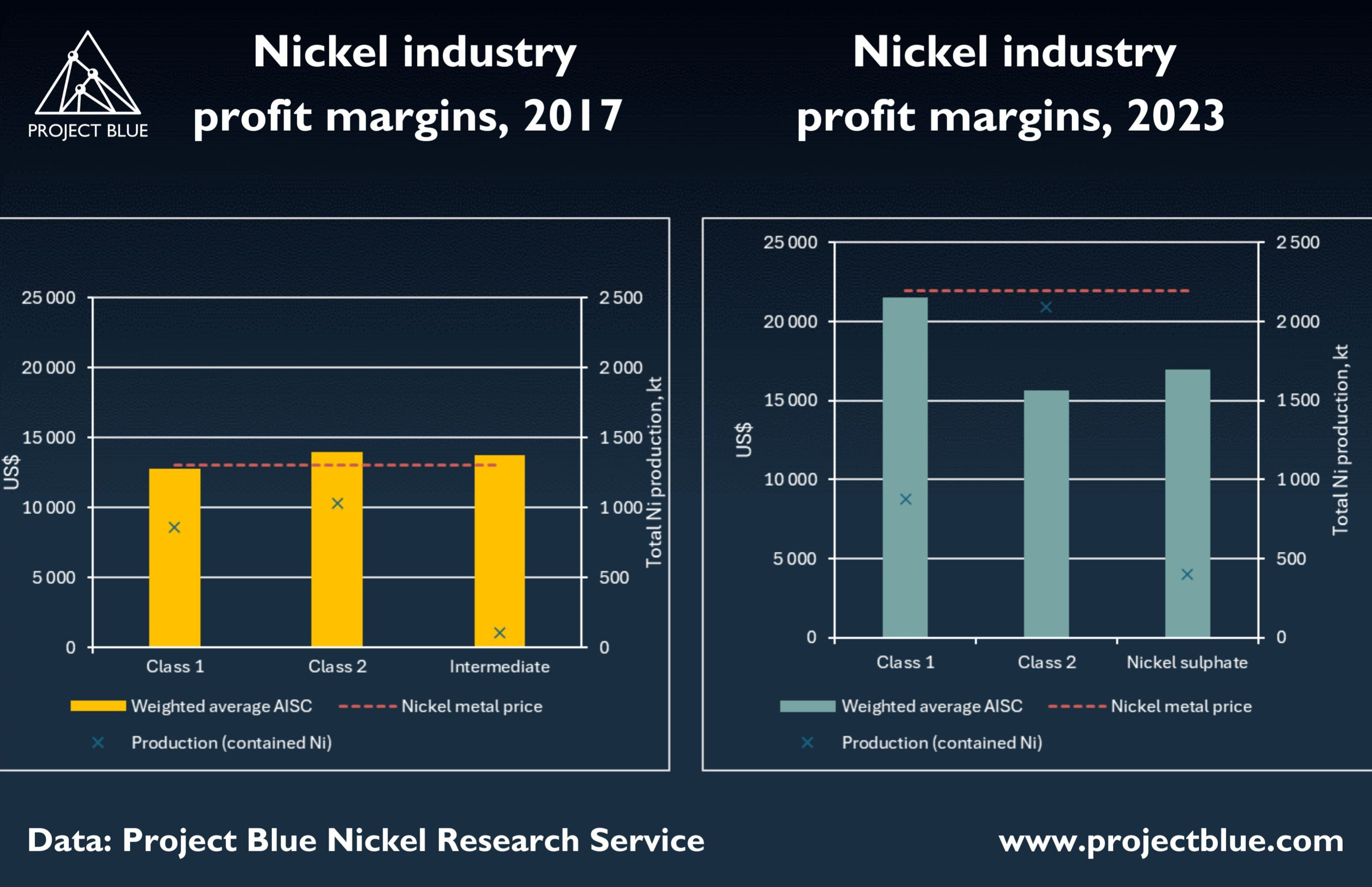

In total, Class II nickel products accounted for 62% and 52% of the market share in 2023 and 2017, respectively, compared to 25% and 43% for Class I nickel products, with the difference made up by nickel sulphate and salts increasing by 7% from 2017 to 2023 (driven by the ramp-up of nickel matte and MHP feedstock production routes). This shows the impact of the shift to NPI on the refined market, meeting both the demand of the Chinese stainless steel sector and creating cheaper alternative intermediates for refined products. This has been a direct result of the lower cost of extracting and processing laterite ore. Between 2017 and 2023, nickel metal prices rose 69%. During this period, Class I producers’ costs increased linearly, rising 68% as operators struggled to maintain limited margins. Additionally, Class I nickel products only saw a production increase of 2%, compared to the 103% production growth of Class II products, where NPI represents 65% of the Class II market share. Comparatively, Class II costs only increased 11%, indicating significant margin growth, with intermediates costs also recording a modest increase of 23%.

Survival of the cheapest

As Project Blue recorded in its extractive cost analysis, Chinese investment in Indonesia has created clear winners and losers. Here, parallels can be drawn within the refined sector. Similarly, Russia, Indonesia, and China dominate the lower quartiles of the refined cost curve, reporting strong margins. The former leans on its significant copper, platinum group metals (PGM), and palladium by-product credits, with the latter two both benefiting from low-cost laterite ore feedstocks. Through China’s involvement in the Indonesian laterite market and its naturally cheap extraction methods, the margin percentage on a country basis has increased from -10% to 22% and 18% to 33%, respectively, while production levels have increased considerably.

The material losers can be identified as either non-laterite producing countries, where they are doubly affected by both higher-cost feedstocks and declining demand for Class I nickel, or countries facing governmental/socioeconomic issues. Australia, a high-cost producer of Class I nickel, was poorly positioned to respond to the rise in Indonesian supply. It has since seen a decrease of 15% in its total production, where margins have been underwater since 2017. New Caledonia continues to experience civil unrest, limiting ore production as pro-independence activists strive to impeach French rule. Impact on the cost profile of local assets predates this analysis and more recently forced the closure of Glencore’s Koniambo asset, responsible for 38% of New Caledonia’s refined production. Finally, occurring as a slight anomaly, Japanese refineries, albeit marginally loss-making, improved their margins, benefiting from an increased nickel price while leveraging laterite ore from New Caledonia and intermediates from the Philippines and Indonesia.

A similar story throughout nickel…

Analogous to Project Blue’s analysis of the extractive sector, global refined costs and their associated margins are intrinsically linked to Chinese investment in Indonesia owing to Indonesia’s strict trade policies over the past decade. The development of NPI and the continued increase in demand from the Chinese stainless steel sector and, more recently, the battery sector look set to fuel this trend into the future. However, as noted in our prior work, this level of Chinese investment in Indonesian nickel processing capacity may jeopardise the chances of the USA ever offering tax incentives under the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) for Indonesian-sourced nickel. Assessing the downstream impacts of reduced Indonesian NPI production on refined nickel products is challenging, especially compared to the extractive nickel industry, due to the diversity of refined nickel feedstocks and end products. Hypothetically:

- Could there be an advancement in the buildout of new refineries where Chinese investment is limited? If so, could the Philippines or New Caledonia offer a solution to the decreased laterite supply required to support the growing battery sector?

- At its current level of production, Indonesia heavily controls price through supply. If production were to decrease, a consequential price increase could create a more cost-competitive landscape for the global nickel sector and the different product forms. In turn, would the market look to sulphide ore in the production of intermediates again, as opposed to NPI-produced mattes, liberating the likes of Australia? Currently, known sulphide deposits are unable to meet this demand; however, this may lead to increased investment in exploration.

- Finally, could interventions such as the EU Battery Regulation offer an arm of support to schemes such as the IRA? Essentially forcing manufacturers (notoriously focused on lower costs) to be transparent regarding their supply chains and procurement. Additionally, this gives power to the consumer, who can hold manufacturers to a higher standard, albeit potentially at the cost of the consumer.

Ultimately, with Indonesia and China accounting for 100% of global NPI supply, a large-scale change to the status quo of the nickel market seems unlikely. Although, as was the conclusion with the extractive market share, an unwillingness to limit Chinese investment could reduce the attractiveness of nickel from Indonesia. Looking forward, OEMs along the value chain may seek to maximise the benefits available from IRA incentives and adhere to stricter environmental regulations.

As highlighted in this review, our cost service offers a current and historical analysis across the market, giving the user a detailed breakdown of individual assets with the ability to compare and adapt the data to their needs.

Our analysis aims to showcase these features while providing insight into the current landscape of the nickel market, how our data can be used to draw coherent and structured hypotheses about supply-side dynamics, and how costs may shape the market share of production looking forward.