China’s C919 aircraft pushing into Airbus and Boeing territory

Opinion Pieces

10

Jan

2025

China’s C919 aircraft pushing into Airbus and Boeing territory

Chinese state-owned COMAC opens offices abroad and pushes for overseas certification as it increases output of C919 jets with aims to capture south-east Asia travel routes by 2026.

The COMAC C919 made its maiden flight in 2023 and has since seen significant capacity development with COMAC delivering ten C919 aircrafts to Chinese customers as of December 2024. The ramp-up of a newcomer to challenge the European-US Airbus-Boeing duopoly comes as air travel is rebounding from the COVID-19 pandemic downturn. Moreso, the timing matches with supply-chain issues for both manufacturers as certifications and safety concerns remain high since two fatal crashes of the Boeing 737 Max aircraft model in 2018. Unfortunately, the woes for Boeing have continued in 2024 with ongoing safety issues and most recently a further crash occurring in South Korea in December 2024 – though not of the Max series.

The COMAC C919 is built to compete against the narrow body Neo and Max aircrafts, though it has a shorter range of less than 5,600km, compared to the Airbus Neo’s 6,300km. Currently, the C919 uses an engine built by CFM International, the largest jet engine manufacturer by alloy weight according to Project Blue’s data. A forecast drop in Boeing’s 737 Max deliveries this year will see CFM International lose market share in 2025, however, remaining the leading consumer of superalloys used in jet engines.

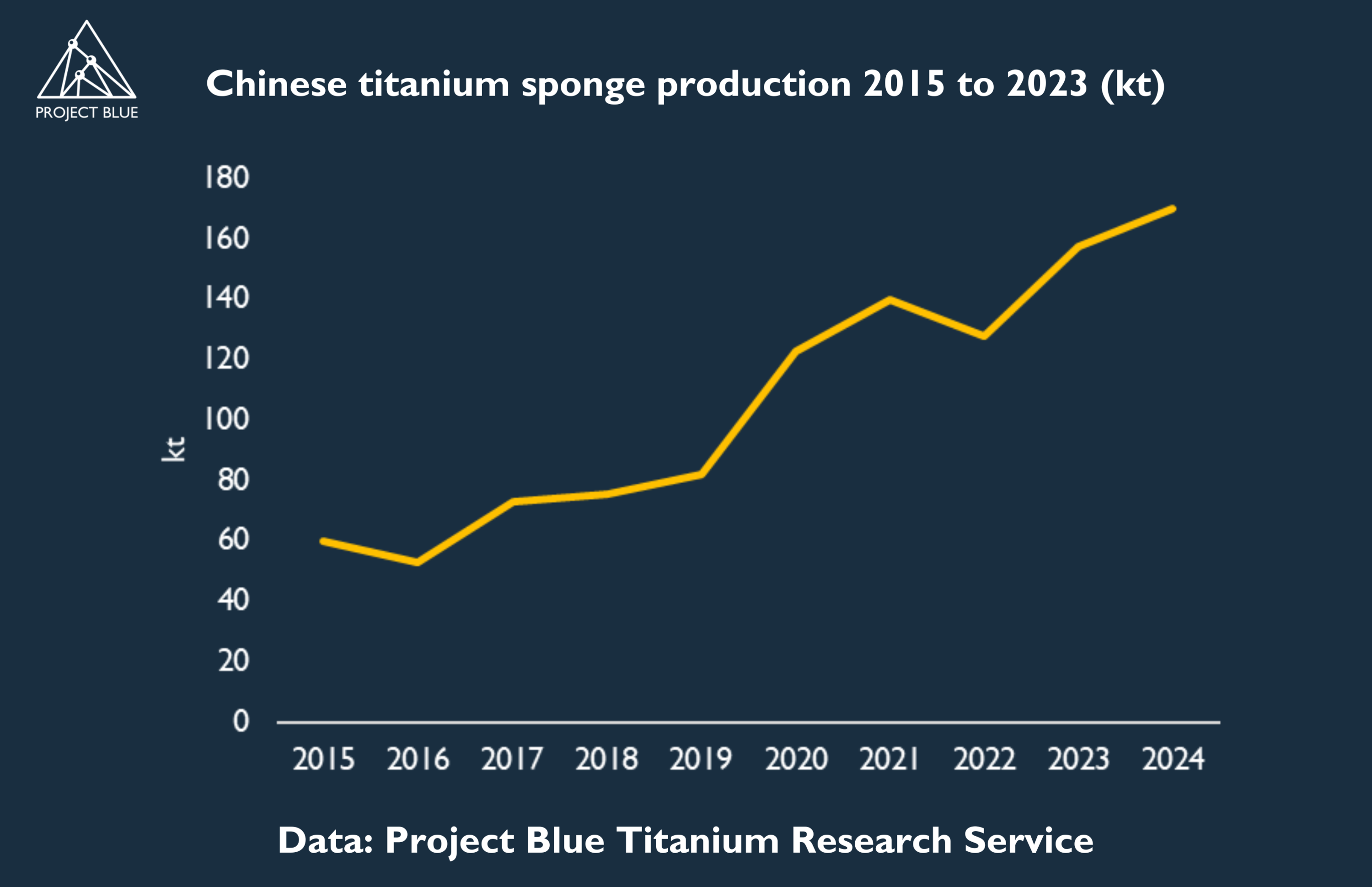

To stimulate its aerospace industry, China has ramped up titanium metal production and soaked up stockpiles of rhenium over the last few years. The importance of rhenium to high-pressure and high-temperature aircraft engine parts is likely linked to China’s growing imports of rhenium stocks over 2024, which caused a shortage in the supply chain outside of China. With rhenium currently only extracted as a by-product from molybdenum processing, itself mostly a by-product of South American copper mines, links together a broad set of critical materials to developments of the Chinese aerospace industry supply chain.

Titanium metal prices are currently low with the aerospace industry still in surplus. The surplus has been exacerbated by the rapid ramp up in Chinese industrial titanium metal capacity, while the downturn in aircraft deliveries struggles to recover. China’s market share in titanium metals production has soared from around 30-35% in the 2010s to over 60% since 2021.

Aerospace-grade titanium metal is predominantly produced in Russia and both Airbus and Boeing are critically reliant on Russian aerospace-grade titanium metal. Russian exports have been under political pressure with sanctions in place, however, titanium metal for the aerospace industry remains exempted from sanctions due to the supply chain reliance. A further twist in this supply chain, is Russia’s own reliance on titanium minerals from Ukraine, historically its largest source and supply has dwindled since the start of the war.

Over 2024, trade in titanium products between China and Russia has ramped up. China, itself reliant on imports of titanium minerals, has built up a stockpile and has supported Russian titanium metal production in 2024 with re-exported feedstock. As China looks to build out its own aircraft jet engine programme, we expect to see Chinese titanium metal capacity convert to aerospace-grade, a task more easily achieved with Russian collaboration.

As a result of the converging factors outlined above, COMAC could become a serious thorn in the supply chains of Boeing and Airbus, at risk of losing access to crucial aerospace-grade titanium supply from Russia. While China’s jet engine programme is still in its forming stage and Boeing deliveries track below expectations, CFM International will benefit from its supply chain agreement with COMAC, which is looking to ramp up its aircraft delivery capacity. In addition, COMAC will use its domestic base to challenge the market share of the duopoly in the fastest growing market for air travel – Asia.