Can the Philippines replicate Indonesia’s nickel ore export ban success?

Opinion Pieces

11

Feb

2025

Can the Philippines replicate Indonesia’s nickel ore export ban success?

The Philippines is set to prohibit raw mineral exports in a bid to incentivise investment in domestic processing, enhance higher-value exports, and create jobs. However, it will be challenging for the country to copy Indonesia’s success story in the nickel market.

The Philippines’ export ban, introduced as part of Senate Bill No. 2826, was approved on its third and final reading by the Senate on 3 February 2025. If signed into law, it will take effect following a five-year transition period to allow mining operators sufficient time to establish processing facilities and develop downstream industries.

The Southeast Asian nation is the world’s second-largest producer of nickel ore after Indonesia, accounting for 10.5% of the global total in 2024. Currently, a significant portion of the Philippines’ output is exported in its unprocessed form, primarily to China’s nickel pig iron (NPI) industry, with the remainder consumed at two domestic high-pressure acid leach (HPAL) plants. In a notable development last year, increasing volumes of ore were exported to Indonesian smelters that were short on domestic feedstock. According to Chinese customs data, China imported 34.5Mt of nickel ore from the Philippines in 2024, representing over 90% of China’s total nickel ore imports. During the same period, Indonesia imported 10.2Mt of nickel ore from the Philippines.

Within the context of heightened geopolitical tensions between China and the USA, as well as ongoing international trade tensions, the ore export ban could serve as a strategic opportunity for the Philippines to attract Western investors to develop domestic processing capacity. These players are increasingly concerned about China’s dominance of the nickel supply chain feeding the EV battery sector and are seeking suppliers that comply with the requirements of the USA’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA).

The Philippines could be well-positioned to benefit, particularly as it already supplies nickel intermediates in the form of mixed sulphide precipitate (MSP) to Sumitomo Metal Mining’s (SMM) IRA-compliant nickel sulphate operations in Japan. The USA has also demonstrated interest in the Philippines, which has not been discrete in touting itself as the “non-China/Indonesia” supply chain. In February 2024, the then-Secretary of State for Economic Growth, Energy, and the Environment, Jose Fernandez, visited the Philippines, representing a clear demonstration of the USA’s intent.

However, efforts by US interests to secure the upstream sectors of the nickel supply chain would necessitate collaboration with partners possessing the technical expertise required to hydro-metallurgically process low-grade laterite ores into battery-grade nickel intermediates. This technical know-how, which has been expertly honed by Chinese entities, including ENFI and Huayou in Indonesia, is also demonstrated by Japan’s SMM, which operates the Coral Bay and Taganito HPALs in the Philippines.

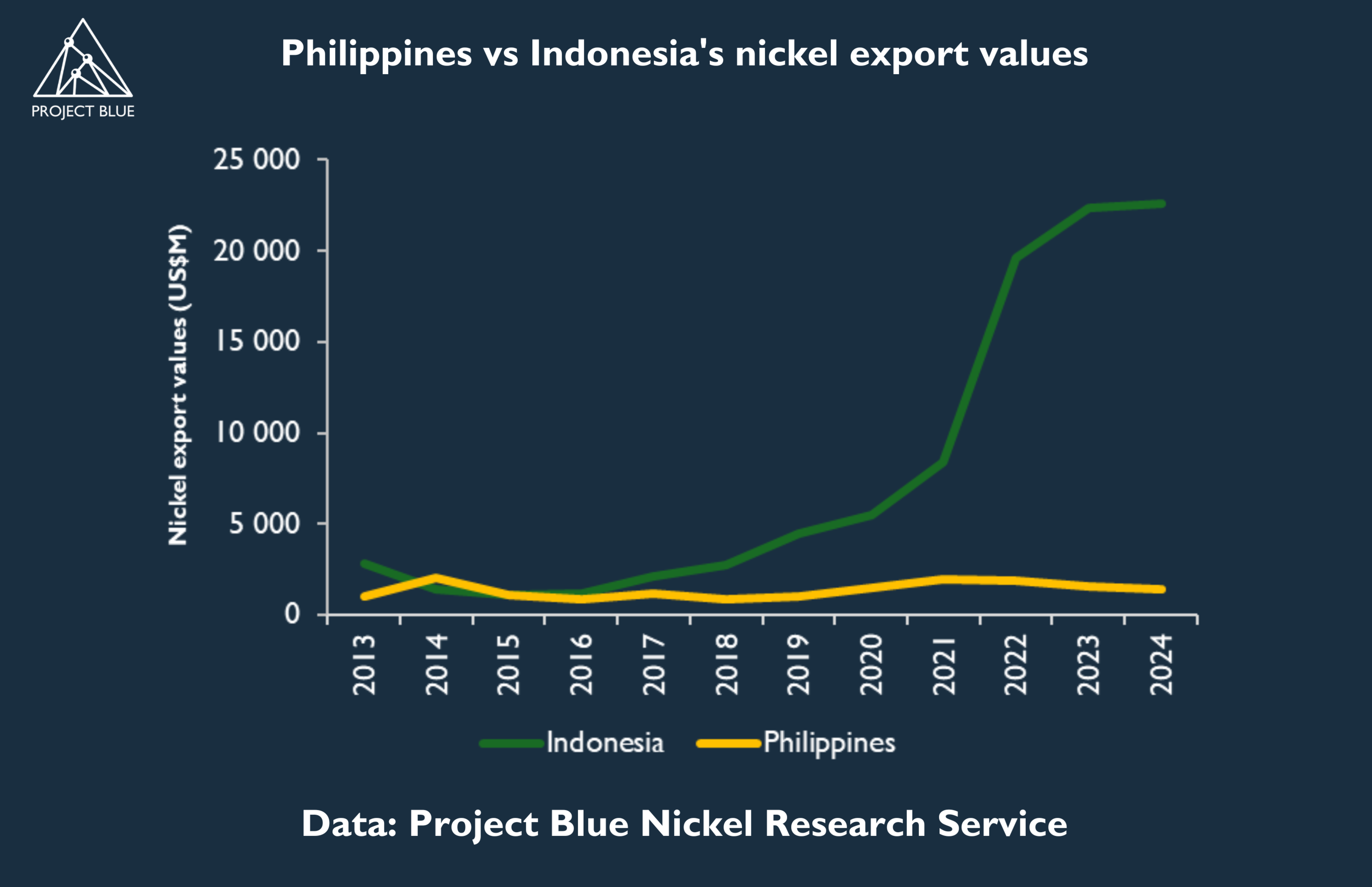

Ultimately, the Philippines’ proposed ban aims to follow Indonesia’s lead after it initially halted nickel ore and bauxite exports in 2014 and developed its domestic refining capacity by effectively forcing downstream investment in-country to secure nickel units.

However, replicating Indonesia’s success presents a massive challenge for the Philippines. On the supply side, the country lacks well-developed infrastructure, as well as sufficient low-cost coal resources to generate the electricity required for nickel refining. On top of this, its nickel ore grades are typically lower than those in Indonesia. On the demand side, the global nickel market, particularly the Chinese stainless steel sector, is currently oversupplied. Moreover, the current low nickel prices present a significant obstacle to securing investment interest in this area. Consequently, there may not be adequate market incentives to support the development of new refining capacity within the Philippines.

In addition to the uncertainty surrounding the development of the downstream nickel supply chain, the Filippino government is expected to face significant pressure from the local ore mining industry. This sector is likely to experience substantial short-term economic losses and reductions in employment if the proposed ore export ban were to be implemented.

Indonesia’s aggressive ore export policy was an integral part of the country’s rise to nickel industry dominance for several reasons. First, the timing was particularly advantageous. During this period, China was actively expanding its Belt and Road Initiative, backed by substantial financial resources for international investment. Simultaneously, the increasing Chinese demand for stainless steel and EV battery materials placed Indonesia, home to the world’s largest high-grade nickel ore resources, in a position of strong bargaining power. In contrast, the Philippines is unlikely to exert similar influence over decisions made by the USA and Japan.

Second, differences in investment approaches between Western and Chinese entities play a significant role. China’s investment in Indonesia’s nickel sector does not rely on short-term gains or high profits related directly to nickel production. Instead, it focuses on long-term advantages and domination of the downstream supply chain, such as EV batteries, as well as broader strategic national benefits. For instance, companies such as Tsingshan and CATL have invested heavily in Indonesia’s nickel mining and refining sectors as part of their vertical integration strategies to secure raw materials for stainless steel and batteries. Conversely, many Western counterparts, such as SMM, lack downstream business operations to capitalise on long-term benefits related to investing in the upstream nickel supply chain. Furthermore, conventional commercial investment models used by Western companies, such as Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) analysis, tend to undervalue long-term profits, discouraging investment in nickel mining projects.

It remains to be seen whether the Philippines can be as successful as Indonesia after taking a bold export stance. While US investment in nickel ore could play the same role for the Philippines that Chinese investment did for Indonesia, it is not enough on its own – the USA must also develop a strong downstream battery market. However, with Trump increasingly shifting focus back to domestic oil and gas over energy transition, this remains uncertain.