A fragile truce: how could dual export controls reshape the global aerospace industry?

Opinion Pieces

22

Oct

2025

A fragile truce: how could dual export controls reshape the global aerospace industry?

Despite warmer diplomacy between Washington and Beijing, with President Trump and President Xi still expected to meet later this month, underlying trade tensions remain far from resolved.

The US president’s earlier threat to restrict exports of Boeing aircraft parts to China, though not reiterated publicly, continues to hang over the industry. The proposed restrictions were originally framed as a potential response to Beijing’s expanded dual-use licensing controls on exports of some rare earth elements (REEs) and associated technologies.

Whilst such measures may appear targeted and strategic, their combined effect would reverberate across the global aerospace and defence supply chains, potentially disrupting production, investment, and the flow of materials far beyond the two nations.

China’s expansive RE export controls

China’s Ministry of Commerce issued four major announcements (Nos. 56, 57, 61, and 62) on 9 October 2025, establishing comprehensive export controls over the entire RE value chain, from mining and smelting to magnet production and secondary recycling. The controls extend to equipment, processing technology, design data, and documentation, effectively covering both materials and the know-how required to produce them.

Announcement No. 61 specifically expands the scope to include all foreign organisations and individuals. Exporters of REE materials or technologies must now obtain a dual-use licence before shipment, closing long-used loopholes via third-party territories such as Taiwan or Southeast Asia. The regulation covers all REEs except lanthanum, cerium, praseodymium, and neodymium, and even captures products containing as little as 0.1% of Chinese-origin REE content. Additionally, exports linked to military use, sanctioned entities, or advanced semiconductor and artificial intelligence (AI) applications are prohibited outright.

Announcement No. 62 details regulations regarding “magnetic material manufacturing,” including Sm–Co, NdFeB, and Ce-based magnet technologies. Regulations regarding production-line equipment and reagents are detailed in Announcement No. 56, whilst Announcement No. 57 specifies controlled forms of medium and heavy REE, targeting various physical forms, including oxides, alloys, ingots, and sheets.

These measures, which took effect on 9 October 2025 (Announcement No. 62), with further implementation from 8 November 2025 (Announcements 56 and 57) and 1 December 2025 (Announcement No. 61), effectively place the global REE industry under China’s licensing control. A short-term surge in overseas procurement is expected before implementation, followed by months of export delays as licence applications accumulate.

Heavy REE prices are likely to spike internationally whilst softening in China once export volumes fall. The restrictions will make it more difficult for industries outside China, particularly those related to aerospace, defence, and semiconductors, to access materials and technology that are critical for permanent magnets, actuators, sensors, guidance systems, and components used in the high-temperature parts of jet engines.

https://www.projectblue.com/blue/opinion-pieces/1336/china%27s-ministry-of-commerce-announces-enhanced-export-controls-on-rare-earths-

Potential US retaliation and the Boeing dimension

Against this backdrop, Washington’s suggestion of restricting the export of Boeing spare parts to China risks compounding the strain.

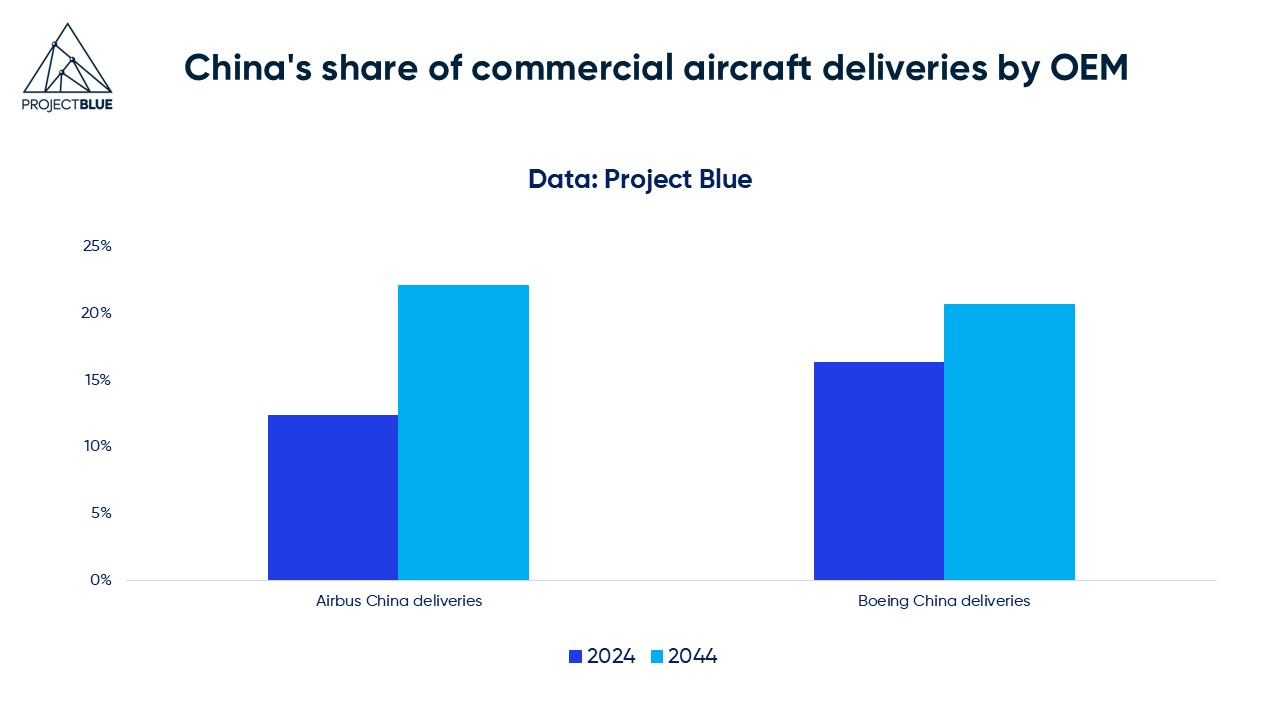

Boeing remains deeply tied to the Chinese market, as Chinese airlines represent nearly one-fifth of its long-term commercial outlook, and negotiations for a 500-aircraft sale were reported to be in advanced stages. Whilst the company delivered 55 jets in September, still trailing Airbus, any formal export limits on parts or maintenance support could undercut both current fleet operations in China and Boeing’s broader recovery after years of supply chain disruptions.

A ban on spare parts or exports would also affect engine manufacturers such as CFM International, the joint venture between GE Aerospace (GE) and France’s Safran, which manufactures the LEAP engine used in the Boeing 737 MAX and COMAC’s C919 aircraft. GE also manufactures engines for the 777 and 787, two larger jets that China has ordered.

Although official rhetoric has softened and high-level talks continue, the spectre of aerospace export controls highlights how easily the sector could be drawn into trade retaliation cycles. Airlines depend on a consistent and reliable supply chain to safely and effectively operate and expand their fleets.

Currently, many airlines are facing unprecedented delays in the delivery of aircraft, engines, and components, along with erratic delivery schedules. These challenges have led to increased costs, estimated by the International Air Transport Association (IATA) and Oliver Wyman to be over US$11Bn this year, whilst also limiting airlines’ capacity to meet consumer demand.

Commercial and raw-material implication

A simultaneous tightening of RE and aerospace exports is expected to cascade through the manufacturing chain. Boeing’s production slowdown would directly reduce US demand for titanium, aluminium, nickel-based superalloys, and carbon composites, pressuring tier-1 suppliers already affected by labour and logistics bottlenecks. However, the slack would likely be redirected to Airbus and China’s COMAC, and potentially Brazil’s Embraer.

Notably, Airbus already has an established footprint in China’s commercial aerospace market and is expanding its assembly lines in Tianjin, as well as in Mobile (Alabama); thus, it is positioned to capture displaced Chinese demand whilst insulating itself from US policy swings.

COMAC, central to China’s push for aerospace self-sufficiency, is working to replace imported alloys, avionics, and systems with domestically produced alternatives as part of Beijing’s broader industrial-independence agenda. Despite progress, the company remains dependent on Western suppliers for critical components, especially engines and flight-control electronics. Its indigenous CJ-1000A engine for the C919 and the CJ-2000 for its future widebody C929, alongside military propulsion programmes such as the WS-15 and WS-19, are still in advanced development stages.

To accelerate progress, Beijing has directed large-scale state investment into jet-engine research, testing, and manufacturing infrastructure. Yet, even with these efforts, China faces significant hurdles in achieving international certification from regulatory bodies such as the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), which is essential for operating aircraft in global markets.

As a result, COMAC is proceeding cautiously, continuing to equip early production C919s with Western engines and avionics until domestic alternatives are fully proven, certified, and capable of meeting international reliability and safety standards.

US export controls on Western-supplied parts for the C919 have significantly slowed production of the aircraft. As of September, COMAC had delivered only six of the thirty-two jets Chinese customers expect this year; two each to China Eastern Airlines and China Southern Airlines, one to Air China, and one to an internal subsidiary that performs charter flights. The manufacturer has even reduced its 2025 target from a previously stated goal of 75 to just 25.

Embraer may also benefit; whilst it is a smaller player than Boeing or Airbus in commercial aerospace, it is expanding in China, recognising growth potential. Its E190-E2 and E195-E2 jets are Chinese-certified, supported by a comprehensive after-sales system with maintenance centres, spare parts warehouses, and pilot training.

Thus, rather than a global fall in material demand, a geographic reallocation would emerge, involving slower throughput in the USA, rising consumption in Asia and Europe, and heightened price volatility for key inputs such as titanium sponge, REEs, and high-temperature alloys.

For REEs specifically, the new Chinese controls will restrict the availability of medium and heavy elements used in aircraft electrical systems, magnetics, and advanced propulsion components. Western original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) and engine makers will face longer lead times and higher costs as licensing bottlenecks constrain exports through to 2026.

Defence and strategic manufacturing impact

The US defence sector is legally insulated but materially dependent on China’s critical mineral supply chains. Although defence contractors are prohibited from trading directly with Chinese firms under export control regimes such as the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR) and Export Administration Regulations (EAR), production still relies on upstream materials refined or processed through Chinese-controlled metallurgical networks. Flagship programmes such as the F-35, F-15EX, and hypersonic weapons systems rely heavily on materials such as titanium, nickel, cobalt, and RE magnetic alloys.

Whilst these materials are mined globally, a significant portion of the raw materials, including REEs, undergo chemical processing, separation, and/or alloying in China. This is because China accounts for over 90% of the world’s processed REs and controls approximately 70% of the REE global mining operations. This dependency spans nearly every modern platform.

Permanent magnets, such as neodymium–iron–boron dysprosium-doped (NdFeB–Dy) and samarium cobalt (Sm–Co) magnets, are essential for radar actuators, flight-control systems, missile-guidance fins, unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) propulsion units, and naval sonar arrays. REEs (specifically yttrium-stabilised zirconia) are used to coat turbine blades, vanes, and other components, allowing them to withstand the extremely high temperatures within jet engines, and require ongoing re-application as part of regular maintenance.

Even modest disruptions to the flow of refined RE oxides, magnetic alloys, or high-temperature metals would elevate costs, lengthen production schedules, and increase procurement risk throughout the Pentagon’s industrial base.

Recognising this vulnerability, the US Department of War (DoW) and Department of Energy (DoE) have intensified efforts to localise and diversify supply. In 2025, under the Defense Production Act Title III programme, Washington committed more than US$540M to accelerate domestic projects with MP Materials, Lynas USA, and emerging producers such as IperionX, aimed at building refining, alloying, and magnet-fabrication capacity inside the USA.

These investments are designed to reduce reliance on Chinese imports for both defence and high-technology applications; however, large-scale capacity will take several years to reach maturity. Until then, RE and high-temperature alloy supply remains a strategic vulnerability, particularly for heavy REEs such as dysprosium, terbium, holmium, and erbium, which are used in precision-guided munitions, propulsion systems, and sensor technologies.

Should commercial aerospace activity weaken under prolonged trade or export restrictions, the Pentagon may expand procurement of materials for key programmes, from advanced fighters and missiles to propulsion and hypersonic research, to sustain industrial capacity and protect critical workforces. This would partially offset reduced civilian production whilst driving modest increases in domestic alloy and superalloy demand, positioning defence manufacturing as both a stabilising anchor for the wider aerospace sector and a catalyst for the USA’s long-term strategy of strategic materials independence.

Whilst both Washington and Beijing have signalled a willingness to retain open dialogue, the parallel use of export controls underscores a deepening structural decoupling in critical technology sectors. Meanwhile, Beijing’s recent move to deepen strategic cooperation with France, emphasising aerospace among key areas, underscores a broader global realignment as nations seek to hedge and diversify their partnerships amid mounting trade and geopolitical frictions.