Blue View

Project Blue’s free critical materials analysis - commentary, insight and video in one place.

Refine your search

- Aluminium Bahrain invokes force majeure amid shipping disruptionNEWS

- Sulphur supply chains through Hormuz reveal risks in energy transition materialsOPINION

- QatarEnergy announces aluminium production suspensionNEWS

- Rio Tinto to construct gallium demonstration plant in CanadaNEWS

- Donut Lab releases solid state battery test report: an interpretationNEWS

- Group1 and Michigan Potash & Salt Co sign MoU for Potash-to-Battery supply chainNEWS

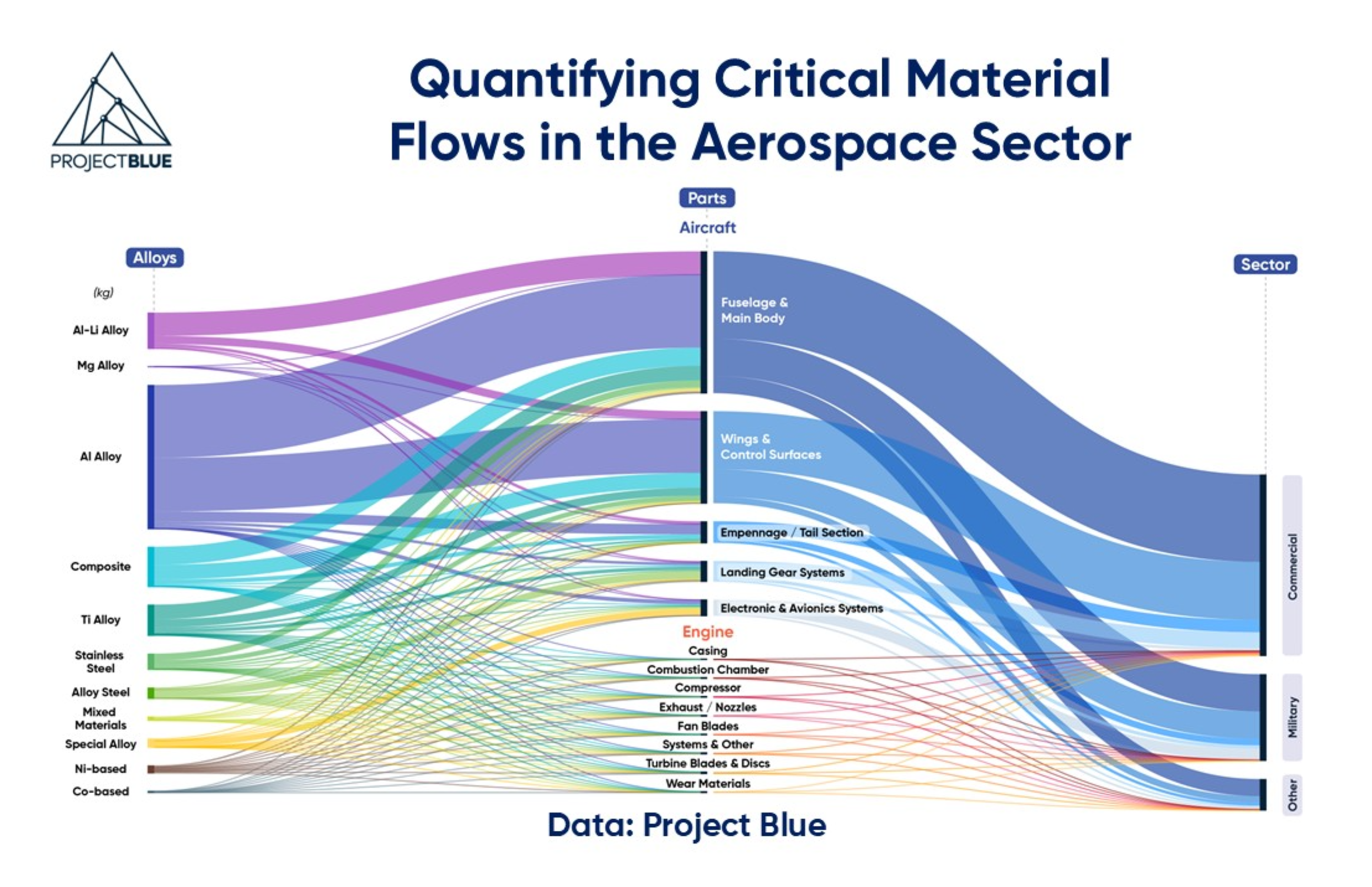

- Quantifying critical material flows in the aerospace sectorOPINION

- Zimbabwe bans lithium exports with immediate effectNEWS

- What is the impact of rising lithium costs on LiPF6?OPINION

- China adds 20 Japanese entities to dual-use export control list NEWS

- Solid-state battery anode materials: technological evolution and industrial trendsNEWS

- Largo is ready to increase vanadium supply to the USA as tariffs are struck downNEWS

- Lion smelter restart follows interim electricity tariff approvalNEWS

- Only US fluorspar mine begins productionNEWS

- Shifting Critical Material World Order: EVs and Li-ion Batteries REPORT

- Securing the Transition: What's Changing in Critical Material Supply Chains in 2026REPORT

- Lithium 2040: The element shaping our futureREPORT

- Trade Tensions and Critical MaterialsREPORT

- Consulting Insights: From Challenge to OpportunityREPORT

- South Africa's Evolving Role in Global Ferroalloy MarketsREPORT

- Critical Materials and the Defence SectorREPORT

- China's 15th Five-Year PlanREPORT

- Copper use in data centresNEWS

- ElevenEs raises Series B to advance Serbian LFP plant NEWS

- Metals and the Security of NationsREPORT

- Sherritt pauses Moa operations in Cuba due to fuel shortagesNEWS

- Metal Markets in TransitionREPORT

- Top 5 Calls for 2025REPORT

- Will developments in China drive tungsten prices to new highs in 2026?OPINION

- Weda Bay Nickel receives sharply reduced 2026 quotaNEWS

- Low cost LFP batteries are outcompeting NCM batteriesNEWS

- Rio Tinto–Glencore: until next timeNEWS

- Project Vault and US supply chain resilienceOPINION

- US Defense Logistics Agency seeks long-term vanadium pentoxide supplyNEWS

- USA bolsters downstream germanium refining capabilities for military applications NEWS

- Canada Nickel’s Crawford Project advanced under Ontario’s “One Project, One Process” frameworkNEWS

- Pangang Group and Dalian Rongke forge 2026 supply pact, bolstering the vanadium flow battery ecosystemNEWS

- CATL’s supply deal with Ningbo Ronbay: impact on the LFP CAM marketOPINION

- EV sector to drive growth in European battery demandOPINION

- Indonesia addresses tin market frenzy with benchmark price NEWS

- IperionX strengthens US titanium supply chain with federal funding and US Army contractNEWS

- US government backs USA Rare Earth to build domestic heavy rare earth supply chainsNEWS

- Rio Tinto–Glencore: copper, coal, and culture OPINION

- Which metals are critical to jet engine supply chains?OPINION

- Alphamin Resources achieves record tin production in 2025 NEWS

- US Government supports strategic fluorspar stockpileNEWS

- Mutoshi sale complicated by competing interests and Gécamines’ entryNEWS

- Zijin Mining and JDC partner to build domestic molybdenum capacity in China NEWS

- Mkango, HyProMag and the University of Birmingham open the Tyseley Rare Earth Magnet Recycling plantNEWS

- Magrathea Metals secures offtake and funding with Wogen ResourcesNEWS

- From dependence to optionality: the USA makes another investment in gallium and germanium NEWS

- High copper prices persist in early 2026NEWS

- Which materials are critical to airframe supply chains?OPINION

- Abolition of administratively determined time-of-use pricing ushers in a new era for energy storageNEWS

- Australia strengthens critical minerals strategy with new strategic reserveNEWS

- PT Vale Indonesia halts nickel ore mining amid delay to 2026 RKAB approvalNEWS

- China moves to ban exports of key critical materials to Japanese consumers under tighter dual-use restrictions NEWS

- Egyptian silicon metal project secures additional financingNEWS

- US must ramp up titanium capacity to avoid squeezeOPINION

- VinFast’s Indonesia bet: regional expansion amid mounting financial pressureNEWS

- PT KNI delivers first autoclave at Indonesian HPAL projectNEWS

- Gécamines and Mercuria form joint venture to commercialise the DRC’s Cu-CoNEWS

- Hype fades as the future of vanadium flow batteries grows uncertainNEWS

- Copper demand to grow 35% by 2035, driven by construction, utility networks, renewable energy and EV sectorsNEWS

- Jervois Global to restart its São Miguel Paulista nickel-cobalt refinery in Brazil NEWS

- Dubai Airshow 2025 highlights: market activity, industrial expansion, and sector-wide challenges NEWS

- Extracting value from waste: the USA pursues domestic scandium and gallium productionOPINION

- Tailings constraints at Indonesian HPALs threaten growing nickel and cobalt capacityNEWS

- Key findings from the 2025 China International Lithium Industry ConferenceNEWS

- Australian Vanadium receives additional funds for vanadium project developmentNEWS

- EV sales continue to climb globally with policy a core driverNEWS

- Vanadium outlook for 2026: Will energy storage offset steel’s slowdown?VIDEO

- Safeguard measures approved for EU silicon and manganese alloys OPINION

- Kazakhstan launches giant ferrosilicon plantNEWS

- Simandou’s first shipment: a three-decade epilogue and a turning point for the iron ore industry NEWS

- Molybdenum market shifts: Copper dependency meets geopolitical tensionsVIDEO

- Ferroalloys in focus: 2025 market review and strategic outlook for 2026VIDEO

- The Project Blue Story: Market Intelligence for the Critical Materials EraVIDEO

- The impacts of suspending the ban on Ga–Ge–Sb exports to the USA OPINION

- Japan’s copper smelters move to consolidate amid margin pressureNEWS

- MinRes and POSCO Holdings form new lithium joint ventureNEWS

- American Tungsten to potentially receive support from US EXIMNEWS

- RHI Magnesita reports ten-month results amid challenging demand backdropNEWS

- How Project Blue’s Consulting team delivers strategic insights for critical material supply chainsVIDEO

- End-of-life battery supply expands: the ABTC is awarded the largest lithium-ion clean-up and recycling contract in EPA historyNEWS

- Successful processing trial at Hemerdon MineNEWS

- Ferro-Alloy Resources appoints contractor to begin construction on Kazakhstan vanadium projectNEWS

- Global ferroalloys leaders reflect on key insights from Project Blue’s Critical Materials Conference: Ferroalloys 2025VIDEO

- US investment firm wins bid to develop Kazakhstan tungsten projectsNEWS

- China’s rise to battery recycling dominanceVIDEO

- EV battery demand: growth, policy shifts, and the recycling imperativeVIDEO

- Regulation takes centre stage in battery recyclingVIDEO

- The rise of battery recycling: ESS and EVs in focusVIDEO

- China’s LB Group tightens hold on global TiO2 capacity with UK acquisitionNEWS

- Outokumpu to invest in a new chrome plant in the USANEWS

- China to suspend rare earth export controls for one year NEWS

- Almonty expands its mining portfolio with US tungsten project acquisitionNEWS

- JPMorgan and Agnico Eagle invest in Perpetua Resources’ US antimony projectNEWS

- European Union includes Evraz on sanctions listNEWS

- Constructive conversations at the 2025 Joburg IndabaNEWS

- Will vanadium supply pressure persist over the near term?OPINION

- Molymet expands in the USA with the creation of Molymet AlloysNEWS

- Korea Zinc doubles up on critical materials with gallium recovery circuit in UlsanNEWS

- A fragile truce: how could dual export controls reshape the global aerospace industry?OPINION

- US and Australian governments to support gallium development with AlcoaNEWS

- Turning policy into progress: monitoring critical mineral commitmentsOPINION

- China’s molybdenum export controls place a spotlight on a strategic metal NEWS

- Tin concentrate tightness persists as Man Maw stays shutNEWS

- Indonesia’s shifting RKAB policy and implications for nickel supplyNEWS

- China’s anti-involution crackdown poses risk to lepidolite supplyNEWS

- China’s Q3 GDP growth of 4.8%: a slowing trend but still in line with Beijing’s objectiveNEWS

- Tightening feedstock availability expected to support cobalt pricesNEWS

- Rethinking secondary aluminium flows in light of global structural demand NEWS

- Copper e-scrap trends: from supplementary feed to strategic resource NEWS

- China tightens export controls on battery materials and core equipmentNEWS

- China's Ministry of Commerce announces enhanced export controls on rare earths OPINION

- Teck Resources lowers Quebrada Blanca copper production guidanceNEWS

- Project Blue Shares Insights on Secondary Copper Market at the ICSG MeetingNEWS

- Global Advanced Metals to supply the US Defense Logistics Agency over the next five yearsNEWS

- Chinese fluorspar capacity expands with new Ka’erqia’er mineNEWS

- Agreement reached between US Department of Energy and Lithium Americas regarding loanNEWS

- Alcoa to permanently close its alumina refinery in Western Australia NEWS

- Vale boosts Onça Puma output with second furnace start-upNEWS

- Accelerating US funding for antimony security NEWS

- Updated Preliminary Economic Assessment for the South Crofty project highlights attractive economicsNEWS

- Freeport-McMoRan declares force majeure at Grasberg mineNEWS

- Ferroglobe suspends silicon metal production in Europe NEWS

- Rio Tinto to supply scandium to the US National Defence StockpileNEWS

- Moroccan chemical manufacturer receives US$110M for its fluorine recovery projectNEWS

- Chinese government sets 180GW target for energy storage installations within two yearsNEWS

- Neo Performance Materials opens Narva NdFeB magnet production facilityNEWS

- China responds to US Department of Commerce adding 23 more Chinese companies to its Entity ListNEWS

- DRC to replace cobalt export ban with quotasNEWS

- China’s integrated circuit production reaches a historic highNEWS

- Superior Graphite has entered into a strategic agreement with the energy giant, ExxonMobilNEWS

- Lopal Technology’s journey of expansion behind the agreement with CATLNEWS

- New graphite supply increases Tanzania’s market shareNEWS

- Aurubis signs a €200M loan with the European Investment Bank to finance copper expansionsNEWS

- US Li-ion recycling: recent developments under policy shifts and price swingsNEWS

- Anglo Teck: from takeover targets to market leaders OPINION

- Portion of Weda Bay Nickel site reclaimed over forestry permit issueNEWS

- Mercedes-AMG debuts quadruple-element lithium battery with revolutionary immersion cooling systemNEWS

- Anglo American and Teck Resources announce a merger of equalsOPINION

- CATL holds meeting to accelerate reopening of the Jianxiawo Lithium MineNEWS

- Talison Lithium moves towards environmental greenlight for Greenbushes mine expansionNEWS

- Critical Materials, Critical Missions: Securing Supply Chains for Defence ReadinessOPINION

- ATI bolsters its aerospace titanium position with a new facility and OEM agreementsNEWS

- JS Link America announces construction of NdFeB magnet facility in Georgia, USANEWS

- US and EU germanium prices surge as material remains scarce NEWS

- Glencore’s layoff plans threaten South Africa’s last stable vanadium operationNEWS

- How will copper miners be affected by the DRC's cobalt export ban?OPINION

- St. Lawrence fluorspar mine restartNEWS

- China fluorspar updates: new mines and expansionsNEWS

- Korea Zinc and Lockheed Martin sign MoU for germanium supply and procurementNEWS

- What’s behind the surge in tungsten prices?OPINION

- Setbacks continue to plague lithium-ion battery cell pipelineNEWS

- US government acquires 9.9% stake in IntelNEWS

- What are the ripple effects of the DRC’s cobalt export ban?OPINION

- EU-USA trade agreement follows new tariffs on over 400 aluminium and steel productsNEWS

- Mozal Aluminium to potentially shut down in 2026NEWS

- Fluorspar search at REE project in MozambiqueNEWS

- Kenyan fluorspar processing plant to be refurbishedNEWS

- CATL expands into battery refurbishment business NEWS

- Digging into copper costs: Concentrate vs SX-EW and the road aheadOPINION

- Copper margins: a decade in reviewNEWS

- Lyten acquires remaining Northvolt assets in Sweden and Germany NEWS

- NextSource & Mitsubishi sign an offtake agreement for coated spherical purified graphiteNEWS

- Do the EU’s antidumping tariffs on Chinese fused alumina imports hinder more than help the domestic sector?OPINION

- CATL halts lithium mineral production at Jianxiawo lepidolite mineNEWS

- SAIC launches its first LMO semi-solid-state batteryNEWS

- Alcoa and Japan Australia Gallium Associates enter joint development agreement for gallium productionNEWS

- Japan and Australia deepen strategic ties with fluorspar MoUOPINION

- New energy demand for vanadium is growing, but South African supply is falling backNEWS

- Export restrictions could reshape manganese market dynamicsNEWS

- Logistics pressures are reshaping chrome export patternsNEWS

- A softer landing for copper tariffsOPINION

- Tariffs still bite while orders build: The US–EU Deal’s Mixed Blessing for AerospaceOPINION

- EQ Resources mid-year capital raising spreeNEWS

- Glencore to close Mt Isa copper mine and smelter NEWS

- Guardian Metal Resources receives US Department of Defense fundingNEWS

- Samsung signs US$16.5Bn deal with Tesla for AI chipsNEWS

- Guinea’s push towards resource nationalisation and its impact on the bauxite marketOPINION

- USA imposes a 93.5% antidumping tariff on Chinese graphite imports NEWS

- Hazer and EnergyPathways enter MoU to develop clean hydrogen and synthetic graphite plantNEWS

- Zangge Lithium suspends mine production at Qinghai operationNEWS

- China restricts export of battery cathode material and lithium extraction technologiesNEWS

- US aluminium tariffs: How quickly can the domestic market adapt?OPINION

- Lifezone Metals releases Kabanga feasibility study technical report summaryNEWS

- China tightens control on gallium processing technology from Bayer liquorNEWS

- Hindalco grows speciality alumina portfolio with AluChem acquisitionNEWS

- MP Materials announces recycled magnet supply agreement with AppleOPINION

- The UK reintroduces EV purchase subsidies to boost adoptionNEWS

- China’s Q2 GDP growth: exceeding expectations, still relying on exports NEWS

- Kazakhstan lifts gallium export dutiesNEWS

- MP Materials and the US Department of Defence partner to expand the US rare earth and magnet industryNEWS

- COMEX ignites: US tariff sparks record copper surgeNEWS

- China Molybdenum's IXM declares force majeureNEWS

- EU reviews anti-dumping duties on ferrosilicon imports from Russia and ChinaNEWS

- South32 exits Cerro MatosoNEWS

- Ferroniobium prices to reduce as Niobec strike comes to an endNEWS

- US developer progresses country’s first alumina plant in over 50 yearsNEWS

- Ferro-Alloy Resources progresses with vanadium project in KazakhstanNEWS

- Critical materials at centre of US-brokered peace deal in Central AfricaOPINION

- Secondary Copper Industries - World Ex-ChinaOPINION

- Eurasian Resources Group (ERG) to start gallium production in Q4 2026NEWS

- China opens the door to “black gold” – Is a massive shift in global battery resources imminent?NEWS

- Implications for critical materials following the 2025 NATO SummitNEWS

- Electra launches early works programme to build Canadian cobalt refineryNEWS

- DRC extends cobalt export ban by three months. What happens next?NEWS

- Greenland Resources secures permit for EU-backed Malmbjerg molybdenum project NEWS

- Vanadium Resources signs supply agreement to finance further development of South African projectNEWS

- Import reliance and the US fluorspar marketNEWS

- AESC starts battery production in France having paused construction of US plantNEWS

- K+S Australia cancels Ashburton Salt projectNEWS

- Micron to increase investment in US Chip supply to US$200BnNEWS

- Kazakhstan to launch yet another ferrosilicon plantNEWS

- Ivanhoe cuts 2025 output guidance and withdraws 2026 forecast as Kamoa-Kakula resumes partial operations NEWS

- CATL cites quality enhancement stance amid ongoing price war NEWS

- Sinomine suspends Namibia’s Tsumeb copper smelter amid concentrate shortage NEWS

- Zimbabwe to implement ban on exports of lithium mineral concentrates in 2027NEWS

- Where next for China's battery cathode materials industry - Part 3:OPINION

- CIBF - The next three years for the battery industry OPINION

- Magnesia’s criticality – has this industry workhorse been overlooked?OPINION

- Where next for China's battery cathode materials industry - Part 2:OPINION

- USA sees more semiconductor investments as GlobalFoundries ups its stake NEWS

- Tariffs on steel and aluminium: doubling down NEWS

- IRH acquires significant stake in Alphamin Resources NEWS

- Glencore restructuring: paving the way for a merger? NEWS

- Large new salt hub planned in Rote Ndao, Indonesia NEWS

- Import reliance and the US fluorspar marketNEWS

- Gabon eyes manganese ore exports ban by 2029 NEWS

- US Battery Costs and the Importance of Tax CreditsOPINION

- Tungsten West reveals requirements for Hemerdon restart NEWS

- Phosphate-fluorine project receives funding in Dazhou, China NEWS

- Where next for China's battery cathode materials industry - Part 1:OPINION

- Falcon Energy Materials and Fluoralpha enter strategic partnership to build a graphite anode plantNEWS

- What next for the cobalt market?OPINION

- Rio Tinto to jointly develop a lithium project in the Salar de Maricunga with CODELCONEWS

- EGA’s Guinea bauxite mining license under threat NEWS

- Steel and aluminium industries react to US-UK metals agreement NEWS

- EGA, RTX, and Tawazun Council agree to gallium exploration in the UAE NEWS

- How will China’s new electricity policy reshape the future of the country’s vanadium redox flow battery market? OPINION

- Shenghe tops up stake to acquire Peak Rare Earths and secure more ex-China feedstock NEWS

- US-based Nathan Trotter secures Rwandan tin supply NEWS

- HUMAIN establishes strategic partnership with AMD, expanding generative AI and data centre applications NEWS

- MP Materials signs partnership with Ma'aden to strengthen rare earths supply chain in the Gulf NEWS

- Due diligence of upstream opportunitiesOPINION

- Exxaro acquires manganese asset portfolio in South Africa NEWS

- Tariffs eased; jets cleared: a global reset for aerospace markets OPINION

- Liontown Resources announces successful application to the WA Government’s Lithium Industry Support Program NEWS

- Strategic Insights: Due Diligence for Upstream OpportunitiesVIDEO

- Finland’s first CAM plant is a major boost to Europe’s cathode dreams, but is its midstream resilience at risk long term? OPINION

- Indonesia finalises nickel royalty hike, adding cost pressure to miners and smelters NEWS

- Rio Tinto and Indium Corp extract primary gallium in Canada NEWS

- Lake Resources aims to increase value of the Kachi projectNEWS

- Almonty Industries pens long-term deal to supply US defence sector NEWS

- USA and Ukraine sign minerals deal NEWS

- Glencore-Merafe suspends additional ferrochrome smelters in South Africa NEWS

- US government grants fast-track status to Resolution copper project NEWS

- USAC’s Madero antimony smelter in Mexico restarts NEWS

- China posts strong Q1 GDP performance, while the next few quarters will be weaker NEWS

- Tariffs, uncertainty, and strategic patience: key takeaways from Seoul battery supply chain discussionsNEWS

- Boeing caught up in USA–China tariff war NEWS

- FQM invests in Prospect Resources to advance Zambia’s Mumbezhi copper project NEWS

- China strategically lists HPQ ore as 174th mineral resource type NEWS

- The Blue View of CESCO Santiago 2025 NEWS

- Aluminium to power French data centre? NEWS

- Scania acquires Northvolt Systems’ Industrial Division to expand off-road electrification NEWS

- Lithium Argentina and Ganfeng Lithium execute letter of intent to advance 150ktpy LCE of projects in Argentina NEWS

- Liontown Resources announces successful commencement of underground mining NEWS

- Alphamin Resources announces phased mining resumption at Bisie NEWS

- Australian developer, Tivan, expands upstream fluorite portfolio NEWS

- China’s tariff on US copper scrap imports to impact the entire copper value chain NEWS

- RUSAL posts 185% profit growth amid aluminium market volatility NEWS

- Malaysian Smelting Corporation temporarily suspends smelting operations NEWS

- Copper Concentrate TC/RC's Hit Record LowsVIDEO

- Intel shifts 3nm production to Ireland while TSMC prepares 1.4nm trial NEWS

- Lithium Americas announces Final Investment Decision for Thacker Pass lithium project NEWS

- Strategic Insights:The Importance of Critical Materials to the Defence SectorVIDEO

- President Trump’s 25% auto tariff sparks global trade concerns NEWS

- PT Amman Mineral to begin copper cathode production by end March NEWS

- Elementos partners with Atlantic CopperNEWS

- Jiangsu Delong's Indonesian assets taken over by Chinese partners NEWS

- Almonty Industries partners with American Defense International NEWS

- South Africa’s ferrochrome industry: facing structural decline or adaptation? OPINION

- Pensana secures US$268M funding for development of Longonjo rare earth project NEWS

- Tronox announces plans to idle Dutch TiO2 pigment plant NEWS

- BYD unveils 6-minute fast charging with 1,000kW peak power NEWS

- EQ Resources pens long-term offtake agreements NEWS

- Aluminium trade uncertainties unsettle the market NEWS

- Carester secures €216M funding for rare earth recycling and refining hub NEWS

- The Economics of By-ProductsOPINION

- Panama allows First Quantum to export Cobre Panama’s stockpiled concentrate NEWS

- Alphamin Resources temporarily suspends mining operations at BisieNEWS

- EU to ease emissions targets for new vehicles and provide financial support for sector NEWS

- Indonesia proposes higher mining royalties amid fiscal pressuresNEWS

- Strategic Insights: The Economics of By-ProductsVIDEO

- China’s Tungsten Export Controls ImplicationsVIDEO

- North American PVDF capacity poised for growth NEWS

- TSMC to invest US$100Bn in US semiconductor fabs and packaging facilities NEWS

- St Piran’s Day and the future of tin mining in Cornwall NEWS

- New US plans for antimony chemicals NEWS

- Indonesia’s new foreign exchange and coal export policies: implications for the nickel industryNEWS

- Scaling up: Anglo American and Codelco partner in US$5Bn copper agreement NEWS

- China’s NPC stimulus measures: positive but potentially insufficient NEWS

- Copper tariffs risk rises as US initiates trade investigation NEWS

- What will be the impact of the DRC cobalt export ban? NEWS

- Major Indonesian nickel smelter faces potential shutdown amid parent company bankruptcy NEWS

- BYD announces new 60Ah solid-state battery for EVs NEWS

- Ukraine's Current Critical Materials LandscapeOPINION

- Anglo American offloads nickel businessNEWS

- Xpeng launches first battery electric vehicle in the UK market to initiate a positive 2025 for Chinese OEMs NEWS

- Freyr cancels US$2.6Bn Giga America battery project, pivots to solarNEWS

- 25% tariffs imposed on all US steel and aluminium imports: more trade tensions and inflation risks? NEWS

- Glencore shuts down PASAR copper smelter in the Philippines NEWS

- Can the Philippines replicate Indonesia’s nickel ore export ban success? OPINION

- MP Materials commences trial production of NdFeB magnets in the USA NEWS

- Chinese export restrictions may disrupt indium market NEWS

- Trump’s tariffs – Potential impact on North America's copper marketOPINION

- China - Expanding embargoes and what could be next? NEWS

- China’s economics in 2025 - beware the Wood Snake NEWS

- Nornickel expects higher production in 2025 NEWS

- Hydro and Rio Tinto partner on aluminium carbon capture technologies NEWS

- Keeping it cool with copper tube in AsiaNEWS

- M23 rebel advancement to impact tin and tantalum exports NEWS

- Indonesia export ban: Grasberg’s Q4 decline offset by strong 2024 copper production NEWS

- Salt mining concession signed in Oman NEWS

- Trump Term Two – First Week in Review NEWS

- GHCL 1.1Mtpy synthetic soda ash plant receives environmental clearance NEWS

- New Chinese fluorspar supply in Xinjiang NEWS

- ICL signs agreement with Dynanonic to produce LFP for the European battery marketNEWS

- Metlen Energy & Metals invests €295.5M to boost bauxite, alumina, and gallium output NEWS

- Chile adjusts its medium-term copper forecast amid ongoing challengesNEWS

- Aluminium price ticks up in anticipation of potential EU ban on Russian aluminium NEWS

- China’s 2024 5% GDP growth: a surprisingly high number given an imbalanced economy NEWS

- Lynas Rare Earths reports lower production amid challenging market conditions NEWS

- Airbus’ aircraft deliveries reach new heights NEWS

- Australian Mines up shoots its scandium resources at Flemington site NEWS

- Copper prices drifting sideways, awaiting USA-China trade relations OPINION

- Outokumpu upgrades chromium ore resource NEWS

- China Molybdenum’s copper production aggravates cobalt oversupplyNEWS

- Indonesia locks in 2025 nickel ore mining quota NEWS

- Copper mining on “the roof of the world” - Tibetan Plateau OPINION

- China reduces import tariffs on recycled copper and aluminium NEWS

- ICYMI: China considers export controls on lithium and battery technologies NEWS

- China’s C919 aircraft pushing into Airbus and Boeing territory OPINION

- ICYMI: Jervois Global taken private in rescue deal NEWS

- ICYMI: KoBold Metals raises US$537M in equity NEWS

- Primary vs secondary, the emerging copper market landscape? OPINION

- China proposes new restrictions on exports of lithium processing and refining technologies NEWS

- ICYMI: a review of key semiconductor developments in DecemberNEWS

- Antimony – the US responds to high prices NEWS

- Phoenix Tailings gets backing for rare earths from Yamaha Motors and BMW NEWS

- Honda and Nissan consider merger in response to a faltering EV sales share and growing China presence NEWS

- PowerCo invests into North American Patriot Battery Metals to secure lithium NEWS

- Indonesia aims halt salt imports NEWS

- Chinese battery majors double down on domestic battery production in Europe NEWS

- Is China about to shift from a monetary to a fiscal policy to revive its economy? NEWS

- Syrah Resources’ production campaign at Balama delayedNEWS

- Australian fluorite project awarded grant fundingNEWS

- Aurubis reveals improved financial performance and steady output for FY2023/24 NEWS

- Is Chile losing its dominance in copper mining?OPINION

- CBMM and Echion open niobium battery anode plant in Brazil NEWS

- Is CNMC’s acquisition of Mineração Taboca further evidence of China’s expansion in Latin America? OPINION

- US tightens regulations for 140 semiconductor companies NEWS

- How will the announcements from China impact graphite exports to the USA?NEWS

- What will be the impact of gallium and germanium export bans to the USA?NEWS

- Saudi Arabia’s copper supply set for boost with Vedanta’s US$2Bn investment NEWS

- Alliance Nickel delivers DFS for Australian nickel-cobalt project NEWS

- Steel production flat year-on-year in line with the subdued macro environment NEWS

- US Magnesium to idle operationsNEWS

- Bushveld Minerals’ shares suspended amidst cashflow issues NEWS

- Northvolt bankruptcy demonstrates technical and geopolitical challenges of core battery manufacturing NEWS

- Sayona Mining and Piedmont Lithium enter into an all-stocks merger worth US$623M NEWS

- House of Representatives passes the Critical Mineral Consistency Act NEWS

- EQ Resources bolsters its tungsten position after penning deal to acquire ferrotungsten plant NEWS

- Prony Resources restarts New Caledonian operation after shutdown NEWS

- Chinese players have purchased record volumes of rhenium over the past couple of years. OPINION

- GEM partners with Vale to build new HPAL plant in Indonesia NEWS

- Political unrest in Mozambique shuts key chrome export route NEWS

- Huayou seeks US$2.7Bn for Indonesian nickel plant NEWS

- Georgian Manganese placed on care and maintenanceNEWS

- Trump presidency: the impact on critical material supply chains NEWS

- Volvo Cars looks to buy out Northvolt’s share of jointly owned gigafactory in Sweden NEWS

- Saudi Arabia to expand into Zambia’s copper industry with planned year-end acquisition NEWS

- NextSource’s graphite enters the US and German markets NEWS

- Surging alumina prices cause problems for aluminium producers NEWS

- Cornish Metals secures second credit facility from Vision Blue ResourcesNEWS

- How has Chinese demand for nickel pig iron influenced cost margins and market share of varying refined class products in recent history? OPINION

- Lithium refineries show significant reductions in spodumene feedstock costs NEWS

- Stellantis plans production cuts for combustion engine vehicle to comply with EU regulations NEWS

- Eramet buys-out Tsingshan to take full ownership of Centenario lithium project NEWS

- Nexans invests more than €90M (US$97M) in Continuus-Properzi copper rod line in France NEWS

- Peru’s copper production declines year-on-year despite higher August production NEWS

- New era for rhenium innovation: Molymet announces new technological advancements NEWS

- Rare Earths discussions in Washington DCNEWS

- African Chrome Fields' expansion and market adaptations amid global challenges NEWS

- Copper cathode production halted following Manyar smelter fire NEWS

- Gécamines prepares to ship first germanium concentrates from the DRC to Belgium NEWS

- Spanish Ministry of Industry doubles down on battery investment NEWS

- Antimony projects mobilise amidst record prices OPINION

- Key takeaways from the Joburg IndabaNEWS

- Vietnam establishes strategy to grow semiconductor capabilities NEWS

- Sibelco rushes to re-establish HPQ production NEWS

- Ivanhoe downgrades Kamoa-Kakula’s copper production for 2024 NEWS

- Myanmarese production of rare earths continues to be impacted by heavy rainfall NEWS

- TANFAC completes expansion of hydrofluoric acid plant NEWS

- Atlantic Lithium receives Mine Operating Permit for Ewoyaa project in Ghana NEWS

- Rio Tinto bets on brine with Arcadium acquisition NEWS

- Germanium prices shoot for the moonNEWS

- Ambatovy closes ore pipeline at nickel/cobalt operation NEWS

- Kamala Harris calls for national stockpile for critical materials NEWS

- Tata Electronics and PSMC establish semiconductor partnership NEWS

- Manganese projects get US funding boost NEWS

- US tariffs on Chinese imports in effect from 27 September NEWS

- Ivanhoe Electric’s vanadium redox battery subsidiary secures US$55M Chinese investment NEWS

- MINVEST: USA leads new plans for financing critical materials projects NEWS

- Standard Lithium receives provisional grant for Arkansas-based lithium project NEWS

- US Depertment of Energy awards more than US$3Bn to address gaps across battery supply chain NEWS

- China Daye copper smelter complex suffers fire NEWS

- New Middle East aluminium partnership for Ma’aden and Alba NEWS

- Giyani granted mining licence for Botswana manganese project NEWS

- Globe receives one-year extension for commencement of Malawi niobium mine NEWS

- Mercedes-Benz partners with Factorial to develop solid-state batteries NEWS

- Pensana signs co-operation and offtake with major Japanese group, Hanwa NEWS

- EASA orders Airbus A350-1000 engine inspectionsNEWS

- Mardie Salt and Potash project gets environmental approvalNEWS

- Arcadium Lithium to place Mt. Cattlin mine on care and maintenanceNEWS

- e-VAC Magnetics closes US$335M funding package for US based NdFeB magnet plant NEWS

- Russia considering export restrictions on raw materials including Ti and NiNEWS

- Argentina’s copper mining revivalNEWS

- US defence sector to benefit from strategic EQ Resources and Elmet tungsten partnershipNEWS

- Up to 6Mt of Mexican salt in stockpilesNEWS

- Metro Mining sets new benchmark with record-breaking bauxite shipmentsNEWS

- US sanctions targets Russian metals and mining exports, including vanadium NEWS

- Furnaces at Koniambo nickel operation shut downNEWS

- Ukraine-based Velta secures EU grant to develop eco-friendly titanium miningNEWS

- Southwire's new sustainability report - with enhanced copper credentialsNEWS

- BTR commences production at its graphite anode facility in IndonesiaNEWS

- Boeing halts 777-9 aircraft test flightsNEWS

- Ambatovy nickel plant undergoes debt restructuring planNEWS

- USA launches trade investigations into Chinese tungsten shot importsNEWS

- Join us at the ICDA in November to discuss the future of chromium in South AfricaNEWS

- Tengyuan Cobalt building Ni-Co refinery in ChinaNEWS

- Kazakhstan and Tajikistan combine efforts to develop rare earth resources NEWS

- ESMC officially breaks ground on semiconductor joint ventureNEWS

- Going green – Mitsui to increase low-carbon aluminium offtakeNEWS

- Ford halts Quebec battery project amid shift in EV strategy NEWS

- Texas Instruments set to receive US$1.6Bn in funding for semiconductors NEWS

- How has the rise of Indonesian supply affected the cost landscape for nickel miners, and can other producers become more competitive?OPINION

- Neo Performance Materials sells JAMR and ZAMR processing facilities to Shenghe Resources NEWS

- US fluorspar project marks next stage NEWS

- Chinese Green Energy Plan targets aluminium with renewable energy targetsNEWS

- Copper: Escondida’s union suspends the strike following agreement with BHPNEWS

- Jindal Stainless commissions Indonesian NPI plant ahead of scheduleNEWS

- USA signs US$1.55Bn MoUs with Amkor and SK Hynix for advanced chip packaging facilitiesNEWS

- Manganese: Project Blue visits MMC's EMM plant and HP MSM pilot plantNEWS

- Glencore suspends cobalt "stockpiling" in the DRCNEWS

- What will China’s antimony export restrictions mean for the market?OPINION

- Copper: Escondida on strike as mediation failsNEWS

- Atlantic Tin finalises purchase of SAMINE from Managem NEWS

- Graphite One inks supply agreement with LucidNEWS

- Nobian to start work on new salt sitesNEWS

- Production at Teck’s Quebrada Blanca molybdenum plant ramps upNEWS

- India’s Tata Group begins construction of US$3Bn semiconductor facilityNEWS

- New soda ash plants planned for IndonesiaNEWS

- Ukraine's government announces the sale of UMCC Titanium NEWS

- SAIMM's 2nd Battery Conference in South AfricaNEWS

- Strike at Escondida waiting for the mediation NEWS

- Aircraft engine demand ramping up for Rolls RoyceNEWS

- Improved profitability for Aurubis amid a stable copper marketNEWS

- Neo Performance Materials secures supply contract with major European motor manufacturerNEWS

- Larvotto targets 2026 kick-off at HillgroveNEWS

- Transnet seeks private investment for manganese port NEWS

- Magnesium metal supply agreement terminatedNEWS

- Arafura secure debt funding for the NolansNEWS

- Umicore delays construction of pCAM/CAM plant in Ontario amid market difficulties NEWS

- Tivan accelerates Speewah after fluorine inclusion on Australia Critical Minerals ListNEWS

- Metals X becomes a major stakeholder in First TinNEWS

- Crude steel production updates for H1 2024NEWS

- Copper majors report improved production for H1 2024NEWS

- Indonesia implements SIMBARA tracking for nickel and tinNEWS

- Marula Mining acquires Northern Cape Lithium and Tungsten NEWS

- First Quantum Minerals commences commercial nickel production in ZambiaNEWS

- Shenghe take 50% stake in Peak Rare Earths JVNEWS

- NextSource next stop in Saudi Arabia? NEWS

- The US expands semiconductor investment into Latin America NEWS

- Germanium prices soar amid stockpiling activitiesNEWS

- China’ Third Plenum: focus on ‘high quality development’ NEWS

- European magnesium project makes progress towards permittingNEWS

- China’s MIIT revises key PV manufacturing industry policyNEWS

- BYD signals its strategy for further expansion in the Southeast Asian EV marketNEWS

- US bolsters measures against tariff evasions via MexicoNEWS

- Ground gravity survey for Rum Jungle projectNEWS

- China’s unwrought copper and concentrate imports stay high in June H1 2024 NEWS

- South Korea’s LS Cable & System is to invest US$680M building the largest submarine power cable plant in the USANEWS

- Almonty signs MoU for tungsten oxide plant in South KoreaNEWS

- BHP places Nickel West operations on care & maintenance NEWS

- IperionX and Aperam Recycling collaborate towards sustainable titanium NEWS

- Liontown and LG Energy Solutions agree extended offtake and downstream refinery collaborationNEWS

- Mozambique graphite assets sold to Shandong Yulan NEWS

- Blencowe updates graphite progress with off-take agreement NEWS

- Eramet and Tsingshan begin commissioning at Centenario DLE plant NEWS

- Eramet and Huayou in talks over Indonesian nickel collaborationNEWS

- Kamoa-Kakula reports 187kt of copper in concentrate production in H1 2024NEWS

- South Korean semiconductor exports increase in JuneNEWS

- Financing secured towards fluorspar mine restartNEWS

- Idled Kenyan fluorspar mine restart NEWS

- Lundin Mining to acquire an additional 19% in SCM Minera Lumina Copper ChileNEWS

- China announces new controls on rare earth resources and traceability NEWS

- Where will future aerospace-grade titanium supply come from? OPINION

- MediaTek to invest in 6GNEWS

- Volkswagen to invest up to US$5Bn in American automaker startup RivianNEWS

- German copper semi-manufactures industry still struggling in 2024NEWS

- MediaTek to invest US$368M into 6G technology research.NEWS

- Semiconductors: TSMC receives approval to construct its third 2nm fabNEWS

- Andrada Mining set to restructure tin mine ownership to improve efficiencyNEWS

- New graphite production from Brazil assigned to the USANEWS

- Fluorspar mining licences to be cancelled in Anhui Province after poor safety recordNEWS

- Fluorine:TANFAC to break into the refrigerant gas market NEWS

- Are batteries with a niobium-based anode set to gain market share?NEWS

- Pilbara Minerals releases pre-feasibility study for P2000 expansion at PilgangooraNEWS

- BMW cancels contract with Northvolt for US$2.15Bn of EV battery cellsNEWS

- Chemaf Resources sale opposed by GécaminesNEWS

- Advanced Propulsion Centre estimates UK BEV demand to top 100 GWh by 2035NEWS

- Menar acquires Metalloys ferromanganese plantNEWS

- New 1Mtpy salt project in QatarNEWS

- Elementos bolsters its European tin positionNEWS

- Echion Technologies raises US$37M to manufacture XNO anode materialNEWS

- Is graphite the gateway commodity for further easing of US raw material sourcing restrictions? OPINION

- Vanadium: Bushveld finalises the sale of VanchemNEWS

- EU moves to implement new tariffs on Chinese EVs NEWS

- Tungsten West awarded processing permitNEWS

- US city Fayetteville approves Project AeroNEWS

- Canada classifies high-purity iron, phosphorous and silicon metal as criticalNEWS

- A Trump vs. Biden White House: the impact on critical materials OPINION

- EGA and Chinalco team-up on alumina refinery in GuineaNEWS

- Peru greenlights Cerro Verde expansionNEWS

- Group14 Technologies signs five major offtake agreements in boost to next-generation silicon anode production NEWS

- Mine expansion commences at the Las Bambas copper mineNEWS

- What and how important are the impacts of a 50% US tariff on Chinese solar cells and modules?OPINION

- Semiconductor fabrication plants might see a delay in construction NEWS

- More African manganese offtakes diversify supplyNEWS

- Project Blue reflections on the IMnI conference in OmanNEWS

- China's crude steel production drops in AprilNEWS

- Expansions for Gallois Graphite in Malaysia NEWS

- Battery swapping expands into Columbia for two-wheelersNEWS

- CODELCO and SQM enter partnership agreement NEWS

- Focus to Peruvian projects after Panama difficultiesNEWS

- SVOLT cancels Germany gigafactory amid permitting and policy challenges in Europe NEWS

- SRB preparing to stockpile cobalt metalNEWS

- Project Blue’s takeaway from the ICDA chromium conference in Hong KongNEWS

- BHP – Anglo American takeover bid – Act IV: a 12-point summaryNEWS

- China joins the race to invest into domestic semiconductor productionNEWS

- What impacts will record antimony prices have on the market?OPINION

- New framework agreement for HC Starck Tungsten NEWS

- LME approves first Indonesian nickel brand listing NEWS

- Reflections on the Advanced Automotive Battery Conference in Strasbourg NEWS

- Saudia Group chooses Airbus for large aircraft order NEWS

- Project Blue reflections from the International Tin Conference in MalaysiaNEWS

- Elon Musk to “consider” Indonesia’s EV battery plant proposalNEWS

- The European ferrochrome benchmark gets discontinuedNEWS

- Rio calls force majeure over alumina third party contractsNEWS

- Mild weather leads to Canadian salt mine curtailmentNEWS

- Zijin Mining Group increases copper production target to 1.22Mt by 2025NEWS

- Cobalt congress commentsNEWS

- BYD delays plans for its LFP cathode plant in Chile amid geopolitical tensionNEWS

- New Caledonia unrest threatens to disrupt nickel productionNEWS

- Vanadium flow batteries to shift market fundamentalsOPINION

- Albemarle and Patriot Battery Metals look to end co-operative lithium MoUNEWS

- EU joint purchasing of critical materials could be closeNEWS

- USA ramps up tariffs on Chinese critical materials and energy transition techNEWS

- BHP stalks embattled Anglo American, despite rejection of second hostile bidNEWS

- Umicore and STL sign partnership related to germanium recycling in DRCNEWS

- Stellantis considers Indonesia nickel investmentNEWS

- What is driving the copper price? NEWS

- What do the Panama election results mean for Cobre?NEWS

- Western Copper and Gold secures funding to advance Casino projectNEWS

- Ganfeng acquires Leo Lithium’s remaining 40% stake in Goulamina lithium projectNEWS

- Factorial and LG Chem form partnership for solid-state batteries in the USANEWS

- Syrah commences its first graphite supply to IndonesiaNEWS

- USA initiates ferrosilicon anti-dumping and countervailing duty investigationsNEWS

- Silicon wafer shipments fall as producers adjust inventoriesNEWS

- Cornish Metals’ PEA points towards positive economics for its South Crofty project NEWS

- First US commercial scale Na-ion battery plant starts productionNEWS

- BCI mining lease granted for Australian salt operations NEWS

- Decline in Codelco Q1 2024 output highlights copper supply challengesNEWS

- Ardea Resources partners with Sumitomo Metal Mining and Mitsubishi Corporation at KNPNEWS

- A note from SeoulNEWS

- Honda invests US$11Bn in a North American EV Value ChainNEWS

- A trio of copper smelter-refinery project updates in China, Bulgaria and Uzbekistan NEWS

- Japan investigates anti-dumping into Chinese graphite electrodesNEWS

- What would a BHP buyout of Anglo mean for critical materials?NEWS

- BHP to make call on Nickel West fate by AugustNEWS

- Copper: could the Panama election result change Cobre's prospects?NEWS

- COMMUS cobalt/copper operating license suspended over radiation levelsNEWS

- Energy Fuels to acquire Base Resources to create global critical minerals businessNEWS

- China Q1 GDP growth: stronger than forecast at 5.3% but…NEWS

- NextSource progresses graphite project in MauritiusNEWS

- Romania grants mining concession to Verde MagnesiumNEWS

- Australian primary tungsten producers ramp-up production in Q1NEWS

- How will the booming semiconductor market affect critical materials?OPINION

- ERG shows interest in diversifying its cobalt supply chainNEWS

- Simandou iron ore project development edges closerNEWS

- Hancock Prospecting purchases stake in US Rare Earth producer MP Materials NEWS

- Will new commercial aviation manufacturing out of China shift future aerospace supply chains?OPINION

- Ascend and Elemental form joint venture to boost European battery recycling NEWS

- Eramet & BASF withdraw investment in Sonic Bay refineryNEWS

- Semiconductor onshoring begins as domestic funds are awardedNEWS

- China stainless steel production supports global growthNEWS

- Tharisa keeps annual chromite guidance at 1.7-1.8MtNEWS

- Vinacomin’s US$7.3Bn investment for Vietnamese aluminiumNEWS

- Woodcross Resources set to commence Uganda’s first-ever tin refineryNEWS

- Lithium Corporation looking at fluorspar explorationNEWS

- Tin prices soar as supply squeeze buildsNEWS

- Letter of interest of up to US$1.8Bn for the Stibnite Gold project NEWS

- Vale’s Onça Puma nickel mine operating licence suspended againNEWS

- MP Materials receives US$58.5M to continue development of US magnet facility NEWS

- Will the Taiwan earthquake impact semiconductor supply chains?NEWS

- DRC suspends contractors at ERG copper/cobalt operationsNEWS

- ARM makes Surge Copper acquisitionNEWS

- India - Adani Enterprises’ Kutch Copper smelter-refinery begins productionNEWS

- GM eyes deal with CATL for US LFP battery productionNEWS

- Bentley is the latest automaker to signal an increased desire for PHEVs NEWS

- DRC overtakes Peru as world's second-largest copper producerNEWS

- New polysilicon developments could reduce Chinese dependencyNEWS

- Tropical cyclone hits largest manganese mine in AustraliaNEWS

- China announces first batch tungsten quota for 2024NEWS

- US Export-Import Bank provides letter of interest to rare earth developers in Australia and BrazilNEWS

- Rio Tinto invests US$350M into Rincon lithium project in ArgentinaNEWS

- Glencore releases second Climate Action Transition PlanNEWS

- Vizcachitas copper-molybdenum project slated for 2029 commissioningNEWS

- Honda and Nissan step towards an electric vehicle alliance NEWS

- Rebel group M23 block trade routes out of DRCNEWS

- April 1: Stellar locations to mine antimony and tungstenNEWS

- Australian Vanadium produces its first high-purity vanadium electrolyte for use in VFBsNEWS

- Early 2024 macro indicators present mixed view of Chinese economyNEWS

- Vale Indonesia reportedly planning third HPALNEWS

- Peruvian copper mine output could hit 3Mt in 2024 NEWS

- Alcoa agrees deal to acquire AluminaNEWS

- South Korea maintains push for LFP battery cells as it eyes western marketsNEWS

- The Crocodile River underground chrome mine comes onlineNEWS

- China-based AutoFlight’s Prosperity completes its maiden voyageNEWS

- Japan negotiates potential investment into Ukrainian titanium industryNEWS

- Major Russian ferroalloy plants nationalisedNEWS

- Copper hits highest price since 2023NEWS

- Buenassa gets government funding for cobalt sulphate plant in DRCNEWS

- Wesfarmers and SQM joint venture ‘Covalent Lithium’ begins ramp-up at Mt Holland lithium mineNEWS

- Tesla begins validation of CATL’s LMFP cells NEWS

- Zijin Mining receives green light to expand Julong mineNEWS

- Pensana concludes non-binding term sheet with consortium NEWS

- Surefire Resources signs second Saudi MOU for its vanadium projectNEWS

- Polyus back as world's biggest antimony producerNEWS

- India specifies royalty rate for 12 critical and strategic mineralsNEWS

- Ghana unveils plans for a US$450M JV manganese refinery project with TMINEWS

- POSCO diversifies graphite supply for battery anodesNEWS

- Pakistan salt industry sees $200M investment from US companyNEWS

- MIND ID secures 14% stake in PT Vale Indonesia NEWS

- Gécamines offers to buy DRC copper-cobalt assets from ERGNEWS

- BYD plans to step up investment into the 2-wheeler battery marketNEWS

- Weirton tinplate plant to be put on care and maintenance indefinitelyNEWS

- Idemitsu, Sumitomo Electric and Vecco Group sign VRFB supply chain agreementNEWS

- LG Energy Solutions commits to LFP in its future NEWS

- Project Blue visits South African chromite producersNEWS

- EU signs MoU with Rwanda over critical materialsNEWS

- Syrah commences AAM production in Louisiana, USA NEWS

- Kenya's fluorspar revivalNEWS

- NMG Signs two Parallel Offtake Agreements with General Motors and PanasonicNEWS

- Hasting Technology Metals signs agreement with Baotou Sky RockNEWS

- New fluorochemicals project in South AfricaNEWS

- Could the IEA lead a critical materials stockpiling initiative?NEWS

- Great Salt Lake mineral extraction bill passed by Utah House committeeNEWS

- Glencore to exit Koniambo nickel operationNEWS

- General Motors and LG Chem Sign US$18.8Bn cathode supply dealNEWS

- Tungsten West granted draft permitNEWS

- TSMC to open second manufacturing plant in JapanNEWS

- How could Indonesia’s election influence its resource nationalism strategy?OPINION

- Tower Semiconductor to construct an US$8Bn fabrication plant in India NEWS

- Tazara rail line to get a boost from ChinaNEWS

- How will Glencore's lower output impact cobalt oversupply?NEWS

- Western Australia provides royalty relief to ailing nickel sector NEWS

- China increases total rare earth production quota by 12.5% in H1 2024 NEWS

- Chinese companies increase investments in copper-cobalt JVNEWS

- Epsilon Advanced Materials Acquires LFP Plant in GermanyNEWS

- Globe Metals & Mining completes Kanyika optimisation studyNEWS

- Average TSMC silicon wafer price soar y-o-y in Q4 2023NEWS

- Almonty makes significant progress with Sangdong Project in South KoreaNEWS

- Australian Vanadium and Technology Metals Australia complete mergerNEWS

- The US Department of Defence awards more critical material fundsNEWS

- Tesla announces new gigafactory using equipment from CATLNEWS

- Are European EV sales stuck in second gear?NEWS

- Shenghe’s latest stretch into international rare earth feedstockNEWS

- Firebird Metal’s Chinese manganese sulphate pilot plant operational.NEWS

- Base Resources to close Kwale titanium mining operation in Kenya NEWS

- Nornickel expects another decline in output in 2024NEWS

- Snowsky Salt increasing soda ash and salt capacities NEWS

- Ferrosilicon meets 3D printingNEWS

- LG Energy Solutions invests in Sion Power to develop lithium metal batteries NEWS

- Will China gain more control of the aerospace supply chain? NEWS

- BHP to place part of Kambalda nickel concentrator on care and maintenanceNEWS

- Tata's Port Talbot closure signals accelerating restructuring of the steel industry NEWS

- Chinese JV partner in Kazakhstan's Bakuta tungsten project prepares for IPONEWS

- Leichhardt Industries acquires Rio Tinto’s Lake MacLeod salt NEWS

- Ganfeng and Pilbara amend offtake agreement as Hyundai looks to secure future lithium supply volumes NEWS

- What to expect from China's economy in 2024?NEWS

- Surefire Resources forges vanadium partnership in Saudi ArabiaNEWS

- Australian antimony production slides further in 2023NEWS

- Protests lead to short-term production suspension at SQM’s Salar de Atacama operationsNEWS

- What do Taiwan’s election results mean for semiconductor supply chains?NEWS

- South Korea to invest US$470Bn into domestic semiconductor sector by 2050NEWS

- Ravensthorpe mine suspended amid low nickel pricesNEWS

- US Supreme Court dismisses Alaska’s Pebble Mine revival attemptNEWS

- New collaboration on the development of magnesium alloy for solid-state hydrogen storage. NEWS

- Is 2024 the year that sodium-ion batteries finally emerge as a commercial challenger to lithium-ion?NEWS

- Is the Simandou iron ore saga about to end?NEWS

- Core Lithium ceases mining activities at Finniss Lithium operationNEWS

- Can increased polysilicon and silane capacity outside China compete with the existing Chinese supply chain?OPINION

- Antofagasta Minerals approves US$4.4Bn Centinela expansionNEWS

- FACOR orders new ferrochrome plantNEWS

- What will the latest Boeing 737 groundings mean for metals markets?NEWS

- Allkem and Livent complete merger of equal to form Arcadium LithiumNEWS

- SQM and Hancock propose joint bidding agreement for Azure MineralsNEWS

- ICYMI: Astron and Energy Fuels sign agreement for Donald HMS projectNEWS

- Norsk Titanium announces its novel technology for additive manufacturing NEWS

- Tanzania to enter graphite supply chainNEWS

- Plans to reduce manganese ore output in South AfricaNEWS

- Outokumpu reduces ferrochrome production NEWS

- Protests follow deadly blast at Indonesian nickel plantNEWS

- Ivanhoe Mines makes first shipment on the Lobito Atlantic Rail Corridor NEWS

- Iron ore prices confound the bears (again)…NEWS

- ICYMI: China announces ‘third batch’ rare earth mining and smelting quotaNEWS

- What does Tshisekedi's re-election as DRC president mean for the cobalt market in 2024?NEWS

- ICYMI: Australia updates list of critical minerals NEWS

- Project Blue visits critical material supply chains in JapanNEWS

- Panoramic Resources goes into voluntary administrationNEWS

- Chile wrestles with the opportunity of high lithium demand while still capturing value from its resourcesNEWS

- COP28 signals commitment to energy transition NEWS

- Blue Review of the year OPINION

- Nickel Industries signs matte sales contract with GlencoreNEWS

- US looks to exclude Chinese entities from the Inflation Reduction ActNEWS

- US to diversify its tantalum supply chainNEWS

- Funding signals positive signs for ex-China manganese sulphate supply chainNEWS

- Electrochem Ghana targets additional salt capacity despite local concernsNEWS

- USA updates to 'foreign entity of concern' guidance will impact supply chainsNEWS

- Glencore secures stakes in Brazilian bauxite and alumina assets NEWS

- High performance electric motors for grid applicationsNEWS

- Gécamines may amend terms of joint venture agreements in the DRC.NEWS

- Mercedes’ plan to support South African productionNEWS

- How will the lithium industry impact global tantalum supply? OPINION

- What will lower output at Mutanda mean for cobalt oversupply?NEWS

- First Quantum looks to avoid arbitration at Cobre PanamaNEWS

- Project Blue visits Kalahari manganese fields NEWS

- Does Northvolt’s news spell an opening of the Na-ion floodgates? NEWS

- Nornickel to exit Nkomati JV in South AfricaNEWS

- UK launches Advanced Manufacturing Plan and UK Battery Strategy.NEWS

- FAA greenlights the Boeing 737 Max 10 for its test flight stage NEWS

- Andrada Mining receives Orion investment and renews off-take agreementsNEWS

- Uranium Energy Corporation advances titanium projectNEWS

- Shut down of chromium artery from South Africa will limit ore supplyNEWS

- US DOE strengthens funding package for domestic battery and raw material productionNEWS

- Atlantic rebuts acquisition approach from Assore International HoldingsNEWS

- Indonesia to ‘track’ nickel from next yearNEWS

- Will a change in demand outlook rescue critical materials prices as we head into 2024? OPINION

- EU agrees deal to secure supply of critical raw materials with an increased focus on recyclingNEWS

- Tantalum producer Global Advanced Metals up for sale NEWS

- Salt industry sentiment upbeat as industry players meet in Southern Africa NEWS

- Solar cell prices decline amid rising capacity in ChinaNEWS

- Magnesium alloy for Sony's lightweight lensNEWS

- Permanent magnets to propel electric aviationNEWS

- Neometals withdraws from Vanadium Recovery Project in Finland NEWS

- New port facility to boost South Africa’s manganese exports NEWS

- MP Materials begins sale of separated Nd-Pr compounds from Mountain Pass plant NEWS

- China’s Ministry of Commerce announces new reporting requirements for rare earth exports NEWS

- Shenghe Resources to invest in Vital Metals NEWS

- Airbus Helicopters opens 3D printing facility in Germany NEWS

- Can new tungsten projects offset Chinese declines? OPINION

- LME approves listing of GEM nickel cathode brandNEWS

- Albemarle downgrades forecast profits for 2023, though continues supply increasesNEWS

- By-product graphite collaboration in MalawiNEWS

- Nyrstar to explore for germanium and gallium while zinc mines shutNEWS

- Minas Gerais trying to sell state niobium companyNEWS

- Glencore slashes 2023 nickel and ferrochrome production guidanceNEWS

- Bushveld Minerals to take full control of VametcoNEWS

- How will a ban on PFAS impact future fluorspar demand?OPINION

- Titanium Sands’ Mannar Island project progressesNEWS

- SQM signs binding Transaction Implementation Deed to purchase a 100% of shareholding in Azure MineralsNEWS

- Velta to produce finished titanium alloy productsNEWS

- Hillgrove: Round threeNEWS

- First Quantum vs Panama: throwing a hat into a ring of troubleNEWS

- ERG plans revamp of Comide copper and cobalt operationNEWS

- EQ Resources acquires full interest in Mt Carbine tungsten operationNEWS

- Minerals from Myanmar: Is China’s supply chain portfolio compromised? OPINION

- Chip wars spread into lithium-ion supply chainNEWS

- Zambian copper-cobalt production from tailingsNEWS

- Albemarle withdraws offer from Liontown as Hancock considers its next moveNEWS

- Volt Resources graphite supply to the USA GovernmentNEWS

- Glencore to close Mt Isa copper minesNEWS

- Honor unveils new Magic Vs2 with aerospace grade magnesium alloy body and titanium hingeNEWS

- ERG enters a cobalt supply agreement with EVelution EnergyNEWS

- Vanadium vs Niobium: Diverging paths?OPINION

- Nickel Industries take FID on Excelsior HPALNEWS

- India refreshes royalties for lithium, niobium and rare earth projects NEWS

- Cornwall Resources and Oxford Sigma sign tungsten MOU NEWS

- China Mineral Resources Group negotiating with iron ore minersNEWS

- Talga begins construction of its Vittangi graphite anode plant in SwedenNEWS

- Teck targets year-end for call on metals, coal business splitNEWS

- Barrick Gold invests US$2Bn in Zambian copper mine expansionNEWS

- Hancock further increases stake in Liontown ResourcesNEWS

- Does salt have a key role to play in the Energy Transition? OPINION

- Horizonte Minerals reveals cost overrun and delay at Araguaia nickel projectNEWS

- Date touted for Centerra Gold-owned Thompson Creek mine restartNEWS

- August steel production: China outperforms, driven by exportsNEWS

- Hancock Prospecting ups stake in Liontown ResourcesNEWS

- Vital Metals files bankruptcy for subsidiary Saskatoon rare earth processing facilityNEWS

- Beta has kicked off commercial electric aircraft productionNEWS

- British exploration company targets Moroccan cobalt NEWS

- Appian Capital sale of Brazilian nickel and copper-gold assets collapsesNEWS

- ZimAlloys to restart idled furnacesNEWS

- Could a new DRC-owned cobalt hydroxide plant be a gamechanger? NEWS

- Battery-grade graphite production in AfricaNEWS

- China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology releases rare earth quota for H2 2023NEWS

- Australian vanadium projects merge as VRFB demand ramps upNEWS

- Xiamen Tungsten and China Rare Earth Group continue consolidation of Chinese rare earth industryNEWS

- More logistics disruptions for South Africa’s manganese exports NEWS

- Where will future molybdenum supply come from?OPINION

- UK rolls back on select net-zero policiesNEWS

- Will lower battery materials prices provide a boost to EV market growth? OPINION

- Potential Dampier split with MacLeod Salt sale NEWS

- Italian fluorspar mine set to restart under Mineraria Gerrei NEWS

- Apple iPhones to boost titanium metal demandNEWS

- Philex Mining turns to Zambales for nickel mining in the Philippines NEWS

- Huawei's breakthrough chip spurs US scrutiny and escalates tech warNEWS

- Russia commissions new copper capacityNEWS

- Tungsten West results point to permitting pressures and insolvency riskNEWS

- Ionic RE, LCM and Ford sign partnership agreement for recycled RE NEWS

- US Defense Department dishes out US$110M for critical metals developmentsNEWS

- BCI wins key funding approvals for Mardie Salt NEWS

- Critical materials central to US Vietnam partnershipNEWS

- Malaysia takes steps to ban exports of rare earth concentrates NEWS

- Latrobe Magnesium focuses its magnesium metal supply on the US marketNEWS

- Saudi Arabia in talks to secure metals in AfricaNEWS

- FPX Nickel releases PFS on Baptiste Nickel ProjectNEWS

- FQM and Rio Tinto form JV to develop Peruvian copper projectNEWS

- A PEA for Pebble but no progress on permittingNEWS

- Lithium: Albemarle bids US$4.3Bn for Liontown ResourcesNEWS

- Volt Resources graphite production continues at ZavalievskyNEWS

- What implications does India's Vision 2047 hold for the steel and alloy sector?OPINION

- Mozambique a solution to South African rail woes?NEWS

- Vale teams up with Huayou for another HPAL in IndonesiaNEWS

- How will Gabon’s military coup impact the manganese supply chain?NEWS

- Italian fluorspar mine set to restart under Mineraria Gerrei NEWS

- Record antimony production at OlimpiadaNEWS

- DRC government bid for ERG copper-cobalt assetsNEWS

- The Johannesburg BRICS’ summit: under constructionNEWS

- India to auction critical materials blocksNEWS

- Germany’s US$2.2Bn integrated polysilicon and solar projectNEWS

- Wa State tin mining suspension details emergeNEWS

- JOGMEC securing critical materials from Southern AfricaNEWS

- Perpetua Resources targets antimony trisulphide supply chain for fundingNEWS

- China’s July steel output remained strong despite a weak demandNEWS

- Vietnam continues charge to offer alternative to Chinese rare earth permanent magnets NEWS

- Exxaro to diversify portfolio into critical materials NEWS

- Euro-China agreement for electrical steel signedNEWS

- ICL breaks ground on US$400M battery materials plantNEWS

- USA enforces anti-dumping duties on tin-plated steelNEWS

- IperionX advances permits for Titan project in the USANEWS

- Andrada Mining secures financing through Orion Resource PartnersNEWS

- QPM achieves first nickel sulphate from pilot plantNEWS

- What does H2 2023 look like for critical materials?OPINION

- Eastplats boosts revenue from high chromium pricesNEWS

- EQ Resources gains foothold in European tungstenNEWS

- Australian miners continue to look abroad for downstream capacity build outNEWS

- How could fast-tracked LME brand listings alter nickel market dynamics?OPINION

- Nickel Industries takes stake in PT Huayue Nickel CobaltNEWS

- Pilbara Minerals to develop a lithium intermediate pilot plant NEWS

- Lynas and US DoD sign follow on contract for HREE plant NEWS

- Trafigura seeks new funding for DRC copper and cobalt projectNEWS

- Glencore bets on copper-molybdenum Mara projectNEWS

- Albemarle invests in Canada-based Patriot Battery MetalsNEWS

- Envision e-waste race car revealed in the UK NEWS

- US Department of Energy releases 2023 Critical Materials Assessment NEWS

- LME approves listing of Huayou nickel brandNEWS

- Winter hibernation for ferrochrome plants in South AfricaNEWS

- 2024: The test year for molten metal calcium-antimony batteries NEWS

- Eramet secures US$400.0M lithium marketing agreement with GlencoreNEWS

- Saudi Arabian venture takes stake in Vale’s base metal businessNEWS

- Oman's smelting portfolio expands into silicon metalNEWS

- Rio Tinto signs agreement to establish aluminium recycling joint ventureNEWS

- South32’s Hermosa Project sees non-cash impairment expense of US$1.3BnNEWS

- Allkem gains support from International Finance Corporation for Sal de Vida projectNEWS

- Tata's US$5.0Bn gigafactory will require over 60% of European lithium supply by 2030NEWS

- Why could steel industry de-carbonisation be long and difficult?OPINION

- Stellantis secures US$11Bn for essential semiconductor supplyNEWS

- Syrah Resources cuts production as graphite prices fall NEWS

- The UAE to develop mines in eastern DRC after a US$1.9Bn deal is signed NEWS

- Audi Environmental Foundation funds innovative e-waste recycling research NEWS

- Surge in energy costs for ferroalloys in IndiaNEWS

- Canada to accelerate critical materials mining project permitting processNEWS

- How will the Chinese economy perform in H2 2022?NEWS

- Lundin Mining acquires majority stake in Caserones copper-molybdenum mineNEWS

- IperionX secures recycled feed for US plantNEWS

- Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt commissions $300M lithium concentrator in ZimbabweNEWS

- BCI Minerals signs “battery style” offtake for saltNEWS

- Neometals signs vanadium offtake agreement with Glencore.NEWS

- Central African rail corridor gets investment to access critical materials.NEWS

- BP ramping up the charge for electrificationNEWS

- Namibia’s tin industry on track to join lithium supply chainNEWS

- Glencore mulls acquisition of remaining PolyMet stakeNEWS

- Fluorine unlocking more battery potentialNEWS

- Will SRB cobalt purchasing push prices higher?NEWS

- Stellantis pens nickel and cobalt offtake deal with Australia’s KunikoNEWS

- Mixed outlooks for UK lithium playsNEWS

- Chip wars: China restricts exports of gallium and germaniumOPINION

- How is EV battery demand altering China’s nickel imports?OPINION

- India identifies 30 critical minerals in new list.NEWS

- European ferrochrome benchmark drops for Q3 NEWS

- A new antimony metal plant planned in the USANEWS

- POSCO and CNGR to construct battery materials plant in South KoreaNEWS

- Kosovo nickel plant restarts productionNEWS

- Serra Verde starts commissioning at Pela Ema rare earth mine in BrazilNEWS

- Financial incentives convince Intel to ramp up investment in European semiconductors NEWS

- Latest crude steel numbers signal China’s sluggish demand NEWS

- Volkswagen plans to use silicon carbide (SiC) chips in its EVs.NEWS

- What role does silicon play in the energy transition?OPINION

- Jervois cobalt output benefits from government funding tug of warNEWS

- China extends tax break for New Energy Vehicles to 2027NEWS

- Jervois receives US Government funding to further develop its US Idaho Cobalt OperationNEWS

- CATL to move ahead with Bolivia lithium investments NEWS

- Rusal to invest in alumina production facility on Baltic SeaNEWS

- Australia releases new critical minerals strategyNEWS

- Mineral Resources exits from toll treating agreement with Ganfeng Lithium NEWS

- The Dutch Capital announced a ban on certain ICE vehicles as of 2025NEWS

- Appian Capital Advisory sells Brazilian nickel and copper-gold assets NEWS

- GM and Samsung SDI new US$3Bn EV battery production plant in New CarliseNEWS

- Rio Tinto invests US$1.1Bn to expand low-carbon aluminium smeltingNEWS

- Vitesco to showcase rare earth free motor technologyNEWS

- Australian iron ore miners start positioning for the de-carbonisation of the Chinese steel industry NEWS

- Are critical materials prices set to rebound?OPINION

- China April steel trend reverses after a Q1 riseNEWS

- USA and UK sign ‘Atlantic Declaration’ to improve cooperation of critical materials NEWS

- Automotive Cells Company opens Douvrin Battery Factory in FranceNEWS

- Magrathea raises US$10M funding for its magnesium metal pilot plantNEWS

- European Lithium signs binding agreement to develop refinery in Saudi ArabiaNEWS

- Will BYD overtake Tesla as largest all-battery electric vehicle producer by end of 2023?NEWS

- Will Boss Mining's suspension impact the cobalt market?NEWS

- China and South Korea to boost semiconductor cooperationNEWS

- NioCorp set sights on aluminium-scandium alloy productionNEWS

- New supply line disruption for iron ore and manganese in South AfricaNEWS

- Reports suggest Glencore is working on improved offer for Teck NEWS

- Australia maps critical material mine wasteNEWS

- International Graphite receives funding to develop its Springdale-Collie projectNEWS

- Tshisekedi China visit could have implications for cobalt joint ventureNEWS

- ExxonMobil becomes the latest big-name investor in the lithium project spaceNEWS

- Asia overtakes Europe to become Nornickel’s main marketNEWS

- Jaguar Land Rover to set-up EV battery plant in the UK NEWS

- Ford signs four new lithium offtake agreements to supply its North American electric vehicle targetsNEWS

- Magnesium project among recipients of Australian Government grants. NEWS

- Australia and USA commit to critical materials compactNEWS

- A tale of two strategies: How do USA and EU critical material sourcing strategies differ?OPINION

- More fluorine could unlock cold-climate upside for EVs NEWS

- Battery giant LG Energy Solutions invests US$13.3M in Ontario-based Green Technology Metals lithium projectNEWS

- Vanadium: upside potential but the market should keep its expectations in checkNEWS

- South African rand drops on geopoliticsNEWS

- EGA signs multi-year alumina supply deal with AlcoaNEWS

- GEM and POSCO invest in separate Indonesian matte capacityNEWS

- South32 Hermosa project is confirmed to be the first Fast-41 mining project in the USANEWS

- Minsur's tin profits plunge amidst protestsNEWS

- Chinese EV production and sales have grown by more than 40% in 2023NEWS

- Volt Resources restarts graphite production at ZavalievskyNEWS

- Toyota still stuck in second gear on EVsNEWS

- Allkem and Livent combine lithium operations and expertise in merger announcementNEWS

- Rare Earths: Explaining historical volatility and remaining uncertainty in the market OPINION

- Dolphin Tungsten Mine to start concentrate productionNEWS

- Tesla breaks ground at US-based lithium refinery NEWS

- Maersk pulls plug on deep sea mining NEWS

- Vulcan Energy Resources aims to raise US$74M with new capital share issuingNEWS

- Dusting off an old fluorite mine in Germany.NEWS

- Norsk Hyrdo and Porsche sign supply agreement for low-carbon aluminium NEWS

- Honda and GS Yuasa set to build battery factory in JapanNEWS

- March crude steel production: China rebounds, continuous decline in ROWNEWS

- Bosch invests in USA chips business NEWS

- Rio Tinto expands scandium footprint through new acquisitionNEWS

- Century Aluminium secures majority stake in JamalcoNEWS

- Stellantis agrees nickel and cobalt offtake with Alliance Nickel and takes equity stakeNEWS

- Chinese companies off-shoring polysilicon production for higher-value markets NEWS

- Tin prices fall back after threat of Myanmar supply disruptionNEWS

- Masan High-Tech Materials and EQ Resources sign an MoU to explore tungstenNEWS

- CATL's condensed battery technology set to deliver up to 500 Wh kg energy densityNEWS

- Tanzania secures funding to develop rare earth and graphite projectsNEWS

- Chilean government moves to nationalise lithium industry NEWS

- Two nickel processing plants planned for the PhilippinesNEWS

- CMOC to resume export of cobalt and copperNEWS

- Arafura inks NdPr deal with a global wind turbine manufacturerNEWS

- China Q1 data shows an uneven recoveryNEWS

- UK identifies areas prospective for critical raw materialsNEWS

- BHP’s takeover of OZ Minerals approved by Australian courtNEWS

- Stainless steel plans expanding in Southeast Asia NEWS

- Wyloo Metals and IGO secure land for integrated nickel refining and cathode precursor material facility NEWS

- What does Q1 tell us about the EV sales outlook for 2023?OPINION

- General Motors invests US$50M in Direct Lithium Extraction lithium developer EnergyX NEWS

- Sumitomo Metal Mining plans first use of proprietary lithium extraction technology in 2028 NEWS

- Neometals increases stake in Finland vanadium projectNEWS

- Indonesia offers limited critical minerals free trade deal with USNEWS

- Transnet doubles manganese exports via dedicated corridor, but still far behindNEWS

- Less Common Metals’ heavy rare earth expansionNEWS

- Final construction at Idaho Cobalt Operations suspendedNEWS

- CATL close to mass production of M3P cathode Li-ion batteryNEWS

- February crude steel production data showing divergence in China and rest of WorldNEWS

- China’s H1 2023 rare earth sets the pace for the yearNEWS

- Ford signs deal with PT Vale and Huayou to develop Indonesian nickel projectNEWS

- Sayona Quebec restarts North American Lithium (NAL) mine in Canada NEWS

- Malaysia wins out for the location of a new magnesium plant NEWS

- Liontown Resources rebuts Albemarle’s approach to acquire all outstanding shares NEWS

- Jindal Stainless moves to secure long-term Indonesian nickel pig iron supplyNEWS

- US interest rates: getting closer to the current cycle peakNEWS

- US Supreme Court declines challenge to US steel import tariffsNEWS

- LG Energy Solutions increases investment in US battery facility to US$5.5bn NEWS

- GEM, SK On and EcoPro partner to develop a precursor plant in South KoreaNEWS

- Is lithium demand dropping in industrial applications?OPINION

- Albemarle confirms Mega-Flex lithium processing investment in South CarolinaNEWS

- Teck Resources starting up new moly supplyNEWS

- LME delays reopening of nickel trading during Asian hoursNEWS

- A critical minerals “refresh” in the UK?NEWS

- Europe publishes new critical raw materials list – adding in “strategic raw materials”NEWS

- China's start to 2023: slow but steady NEWS

- Ferrochrome benchmark price up while being squeezedNEWS

- Will lithium-ion put a squeeze on manganese?OPINION

- Volkswagen confirms battery plant to be constructed in Canada NEWS

- China EV sales make a stuttering start to 2023NEWS

- Decision due in Brazilian niobium caseNEWS

- Neometals announces feasibility results for its Vanadium Recovery ProjectNEWS

- More smelter shutdowns in the EUNEWS

- A big week for critical materials policy in EuropeNEWS

- Are battery-grade nickel supply chains diverging?OPINION

- Record molybdenum prices igniting hope for old minesNEWS

- Lithium Americas breaks ground at Thacker Pass after US Bureau of Land Management gives the green light NEWS

- China sets a conservative 5% GDP growth target for 2023: more a floor than a forecastNEWS

- Is CATL betting on falling lithium prices? NEWS

- NanoXplore’s patent for silicon-graphene battery anode NEWS

- Polyus antimony output up y-on-y but not enough to balance marketNEWS

- Tesla points towards rare earth free permanent magnet motorsNEWS

- From "cobalt cliff” to "cobalt cornucopia”?OPINION

- What do China's investigations into illegal lithium mining mean for the market?NEWS

- Plans to ramp up manganese output in IndiaNEWS

- POSCO Group and Lygend plan nickel plant in IndonesiaNEWS